What Europe’s game-changing regulation means for platform competition

Platform Papers is a monthly blog about platform competition and Big Tech. The blog is linked to platformpapers.com, an online repository that collects and organizes academic research on platform competition.

By Damien Geradin and Stijn Huijts, Geradin Partners

The Digital Markets Act (DMA) went into effect last year, creating a new set of rules with which some of the world’s largest digital platforms will need to comply from 6 March 2024 onwards. The DMA aims to make the markets on which these platforms have a “gatekeeper” function fairer and more contestable. Key platforms that will be affected include Apple and Google’s app stores and mobile operating systems, Meta and TikTok’s social media networks, Amazon’s Marketplace and Google’s search engine.

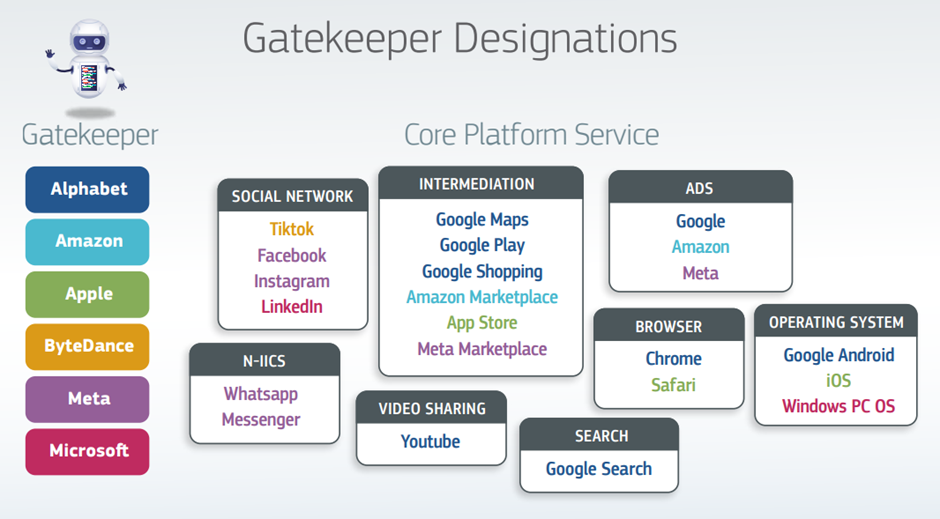

The platforms will be subject to a series of obligations and prohibitions to open up closed ecosystems, introduce interoperability, and ensure business users of the platforms are not treated unfairly. The Commission’s diagram below shows the gatekeepers and the “core platform services” for which they are designated.

The gatekeepers must submit their DMA compliance plans by 6 March 2024. Summaries of those compliance plans, which set out how gatekeepers intend to implement the DMA, will be made public to increase transparency and facilitate monitoring by the businesses that the DMA protects.

The DMA: A necessary and promising set of rules

How did the DMA come about? As readers of Platform Papers will know, two-sided digital platforms have particular characteristics. Network effects, scale and availability of data may mean that it can become near impossible for rivals to unseat a dominant platform, except with an entirely new service that displaces the incumbent. Moreover, some of these platforms are used by hundreds of millions of people in the EU, as well as forming the only gateway for certain businesses to serve those consumers. Finally, the owner of the platform often competes with its business users. Apple has music and TV streaming services that compete with Spotify and Netflix, Amazon retail competes with third-party sellers who use Amazon Marketplace, etc.

Network effects, scale and availability of data may mean that it can become near impossible for rivals to unseat a dominant platform.

In the mid-2010s, the European Commission and various national competition authorities launched investigations under existing competition law provisions to address abuses of the dominant positions held by these platforms. This led, for example, to the Commission’s Google Shopping and Google Android investigations, as well as its investigations into Apple’s App Store, Apple Pay, and Amazon’s Buy Box and use of data. At a national level, landmark decisions were adopted as well, including in France (Google Ad Tech), Germany (Meta), the Netherlands (Apple App Store) and Italy (Amazon Buy Box).

These investigations were influential, but also showed major flaws in the reliance on competition law to deal with deep-seated issues in digital markets. Competition investigations took a long time to resolve, so that the market had often moved on once the authorities reached their decision. They often contained remedies that were so narrow that they did not bring about meaningful change in these markets. It became clear to policymakers in the EU that competition enforcement alone would not be sufficient. Their answer was to adopt a new set of rules, the DMA, that would apply to companies that met certain criteria.

The rules themselves are both ambitious and promising. They allow the Commission to designate companies as “gatekeepers” if they have a significant impact on the internal market, provide a core platform service that is an important gateway for businesses to reach consumers, and enjoy an entrenched and durable position. In practice this is determined on the basis of quantitative requirements which, if met, create a rebuttable presumption. The relevant company is designated specifically for the relevant core platform service: Microsoft is a gatekeeper for its Windows operating system, but not for its search engine Bing. Once designated as a gatekeeper for a core platform service, the gatekeeper will need to comply with the specific rules that apply to that core platform service. They become, in effect, a regulated company.

In each case, the rules address issues identified in the competition investigations and studies carried out in the period before adoption of the DMA. For example, Apple and Google, which have been designated for the App Store and the Play Store respectively (among other services), must allow end users to directly download apps from the web and to install other app stores on their devices. They must also allow app developers to use alternative payment service providers or include a link-out to purchase in their app. They can no longer use data they obtain on their business users when competing with them. Other obligations will apply to services such as search, operating systems, and messaging services.

The proof of the pudding will be in the eating

If the rules are implemented properly and enforced rigorously, they promise to bring about real-world change in these markets. However, there are reasons to be worried about whether the DMA will fulfill that promise.

The Commission will have its work cut out, facing some of the world’s wealthiest companies who have a lot to lose from full compliance, and everything to gain from delaying the full consequences of the DMA.

Some gatekeepers have come out fighting. Three of them appealed the Commission’s decision to designate them as gatekeepers. Some also take a narrow and negative view of their obligations under the DMA. The best example is Apple, which published its plans for app distribution in Europe recently. Apple’s plans undermine the aims of the DMA to make these markets fairer and more contestable. For example, although alternative app stores will be introduced, the rules that will apply to apps that want to use them can be costly, a cost that can be avoided by sticking exclusively to the App Store. As a result, the likes of Uber, Netflix and Facebook may choose not to support new app stores, which will mean new stores will struggle to achieve the scale to compete with Apple.

The Commission will have its work cut out, facing some of the world’s wealthiest companies who have a lot to lose from full compliance, and everything to gain from delaying the full consequences of the DMA. This raises the question whether it has sufficient resources to deal with this mammoth task. While national agencies will have a role in assisting the Commission, only the Commission can make formal findings of non-compliance with the DMA. Just 150 officials are reported to be tasked with DMA enforcement at the Commission. This is not enough to regulate six of the world’s largest companies, who have near infinite resources to cause delay and obfuscation.

Immediate priorities after 6 March

Against that backdrop, what should be the Commission’s immediate priorities after 6 March? This month, the Commission will hold a series of public workshops to discuss the gatekeepers’ compliance plans. Indeed, the lessons from sectoral regulation are that empowered and well-informed stakeholders play a key role in keeping the regulated firms on the straight and narrow. It is right that the Commission views this stakeholder engagement as a priority.

If the Commission dithers at the outset, compliance issues will quickly become highly complex. Armies of lawyers and advisers will tie the Commission down in years of procedural wranglings.

But to avoid losing time and momentum, the Commission must also be willing take immediate action against those gatekeepers who are not taking compliance with the rules seriously. If the Commission dithers at the outset, compliance issues will quickly become highly complex. Armies of lawyers and advisers will tie the Commission down in years of procedural wranglings. Swift, decisive and proportionate intervention will show how seriously the Commission is taking its role under the DMA.

Third, national competition agencies must be given a serious role by the Commission. The DMA gives them the ability independently to conduct investigations if their national governments let them. The Commission should put pressure on national governments to do so. After this, the Commission and national agencies should jointly set priorities and have clear allocation principles. Alignment with the national agencies will show that Europe’s regulators speak with one voice. This will make for effective enforcement and provide more legal certainty to gatekeepers.

Finally, the Commission must facilitate private enforcement of the DMA. Private enforcement refers to businesses or consumers raising non-compliance with the DMA in proceedings before national courts. If these actions are effective, they relieve pressure from the Commission. The Commission should therefore train national courts and be ready to participate in proceedings to ensure that the DMA is applied consistently across Europe.

Geradin Partners are a specialist competition law, competition litigation and digital regulation firm based in Brussels, London and Amsterdam. Their team of lawyers is at the cutting edge of these issues having acted on many of the leading European and UK cases and held senior competition agency positions.

Platform-Paper Updates

Eight new papers have been added to the Platform Papers references dashboard in February. Here are some highlights:

You might have heard that Universal Music Group has been pulling some of its catalog from TikTok after negotiations over contract renewal reached an impasse. UMG demands higher royalty rates, protection against AI-generated music, and improved safety for TikTok’s end users. TikTok is not trying to hear it. This links with a recent study by Jiawei Chen and colleagues in Information Systems Research. Chen et al develop a deep-learning framework for music recommendations on short video sharing platforms (read: TikTok) that takes into account the three-way interaction between the creator of the video, the video itself and the music. They argue that their recommendation algorithm is superior to the ones currently in use by these platforms… That is, if there is any music to recommend, of course!

This segways nicely into another recent study in Information Systems Research by Gorkem Turgut Ozer and colleagues aptly titled “Noisebnb: An Empirical Analysis of Home-Sharing Platforms and Residential Noise Complaints.” Leveraging the phased expansion of Airbnb into different areas in New York City, the authors assess how the emergence of home-sharing platforms affects noise complaints in densely populated urban areas. The headline finding suggests that the arrival of Airbnb is associated with a significant decrease in the rate at which city residents file residential noise complaints. Perhaps there is opportunity to conduct a follow-up study that exploits the UMG-TikTok impasse as an exogenous shock to the supply of noise and influencers flooding the city!

Let me know, please, how you like today’s blogpost, which is slightly different from the usual content? We’ll resume our regular scheduled programming later this month with a blog on intra-platform competition, based on an excellent paper by Oren Resef.

Platform Papers is curated and maintained by Joost Rietveld.