Unintended effects of imposing fee caps on US food-delivery platforms

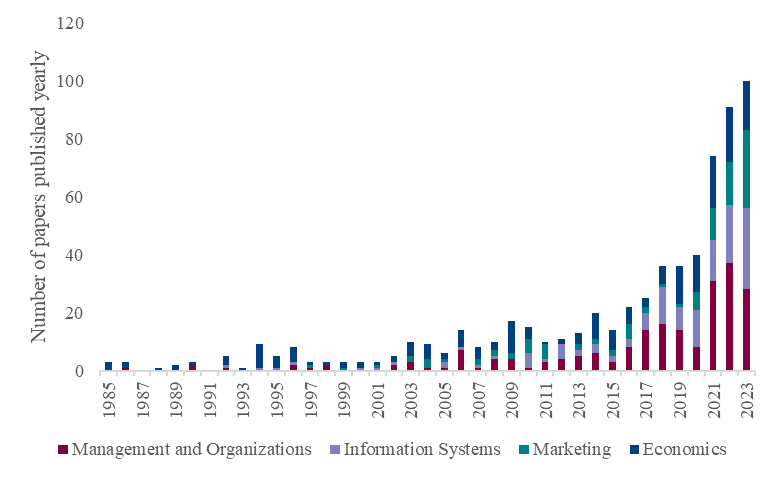

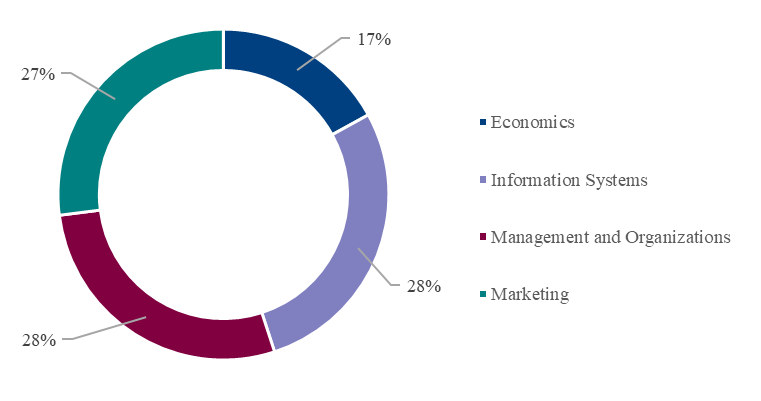

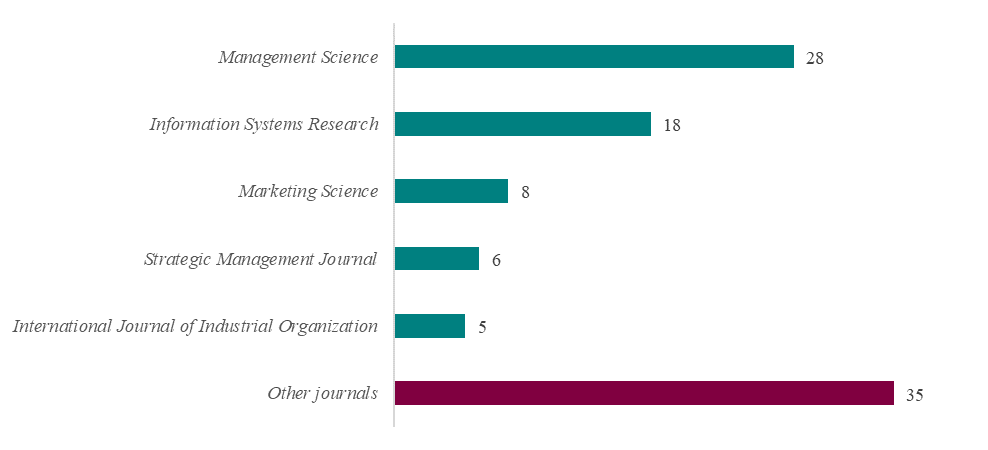

Platform Papers is a blog about platform competition and Big Tech. The blog is linked to platformpapers.com, an online repository that collects and organizes academic research on platform competition.

Written by Allen Li and Gang Wang.

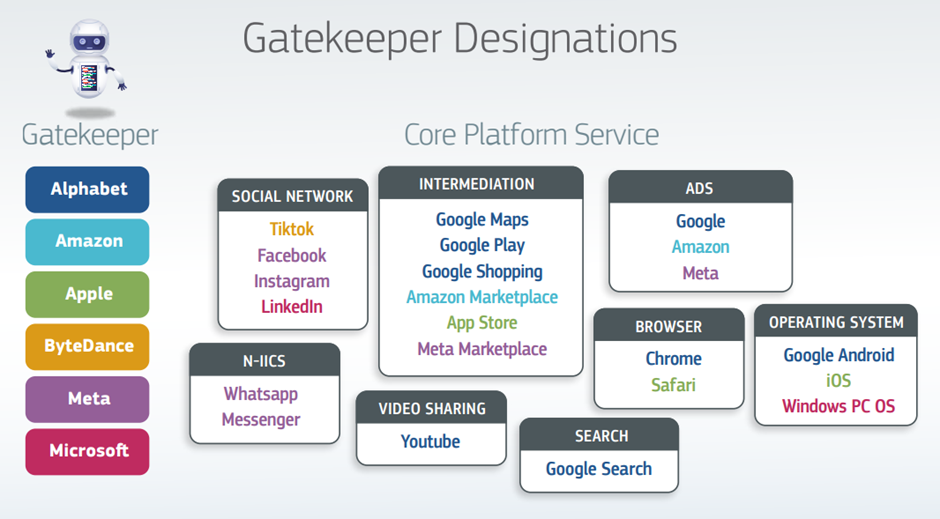

Platform giants (e.g., Apple, Google, and Uber) often possess dominant power over other participants on the platforms (e.g., Apple vs. mobile app developers, Uber vs. independent drivers, and DoorDash vs. small restaurants). Such power asymmetry gives platform owners the edge in setting platform fees and policies to extract the surplus created by participants. Recently, tensions have intensified between these powerful platforms and third-party participants, highlighted by the ongoing legal battles and regulatory actions against platforms. For instance, Epic’s recent lawsuit against Apple accused that the Apple App Store acts as a monopoly, taking a 30% cut on all in-app purchases while banning outside payment methods. Restaurants have also complained that online food delivery apps (e.g., DoorDash and Uber Eats) charge commission fees as high as 30% of sales from delivery orders, eating up their already thin margin. Local and state regulators in the United States have introduced various measures to protect small restaurants, including imposing a cap on what delivery apps can charge restaurants. Ridesharing apps Uber and Lyft have long been accused of underpaying contract drivers, promoting some cities like Minneapolis, Minnesota, and New York City to impose minimal wages these apps need to pay drivers.

“In the EU, the United States, China, and other parts of the world, it has become a consensus that powerful platforms should be regulated. However, there have been heated debates on how to regulate these powerful platforms.”

In the EU, the United States, China, and other parts of the world, it has become a consensus that powerful platforms should be regulated. However, there have been heated debates on how to regulate these powerful platforms. The hard questions are: do regulations work? How do platforms respond to these regulations? For instance, what if regulators impose a cap on fees that platforms can charge small businesses? As digital platforms are quickly evolving, legislatures still have a limited understanding of the potential consequences of such regulations. The lack of empirical evidence hinders the progress toward evidence-based policymaking.

In a recent study of the restaurant industry forthcoming at Information Systems Research, we provide insights into the intended and unintended consequences of regulating online food delivery platforms. The global online food delivery market is a $121 billion business in 2022, and the market is projected to reach $250 billion by 2028. However, high platform fees have increasingly sparked concerns from not only restaurant owners but also policymakers. To support local restaurants, on April 13, 2020, San Francisco became the first city to order delivery platforms to cap their commission fees at 15%, which is about half of the original rate. The regulation covers independent restaurants but not chain restaurants. Similar measures are imposed by dozens of other cities such as Los Angeles, Seattle, Washington D.C., and New York City. Although many of these cities considered commission caps as an “emergency order” to protect small businesses that were hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic, some cities such as Seattle, Washington and Portland, Oregon have decided to make the caps permanent, whereas other cities like San Francisco have gone back and forth—first making the caps permanent but later reversing the action.

“This intriguing finding suggests that chain restaurants, not independent restaurants, benefit from the regulations that were intended to support independent restaurants.”

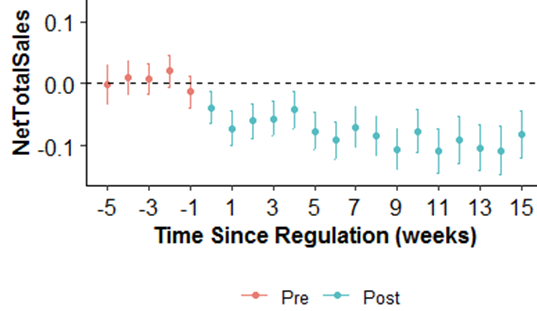

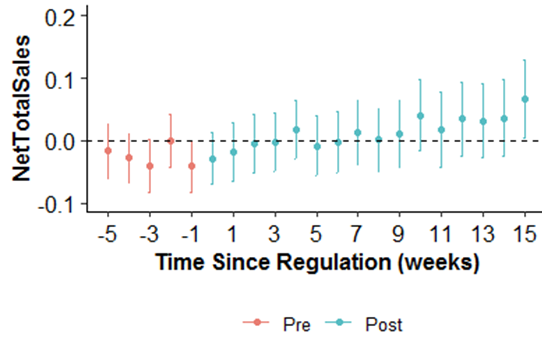

Our empirical analyses show that independent restaurants in regulated cities (i.e., those paying reduced commission fees) experience a decline in orders and revenue (Figure 1), whereas chain restaurants (i.e., those paying the original fees) see an increase in orders and revenue (Figure 2). Net profit for independent restaurants also declines, which suggests that reduced commission fees do not compensate for the loss in orders. This intriguing finding suggests that chain restaurants, not independent restaurants, benefit from the regulations that were intended to support independent restaurants.

“After cities enact commission fee caps, delivery platforms become less likely to recommend independent restaurants to consumers, and instead turn to promote chain restaurants.”

Why do independent restaurants suffer while chain restaurants thrive? Our study explores this question further by collecting additional data from delivery platforms. Our analyses show that how these platforms respond to the regulation can explain, at least partially, the negative impacts of regulations on independent restaurants. First, delivery platforms can tweak the recommendation algorithms to promote chains and restaurants just outside a city’s limits, where they can collect their rates in full. After cities enact commission fee caps, delivery platforms become less likely to recommend independent restaurants to consumers, and instead turn to promote chain restaurants. Second, delivery platforms increase their delivery fees for consumers in regulated cities, suggesting that these platforms attempt to cover the loss of commission revenue by charging customers more.

“Policymakers should consider these second-order effects when developing regulatory policies.”

Alterations of commission fees have also been observed in other platform markets such as Ticketmaster, Steam, and iOS/Android app markets. For instance, facing regulatory pressure, in 2020, Apple reduced its commission rate to 15% for small app developers if they earned up to $1 million in proceeds during the previous calendar year. Our empirical findings highlight the complexity of regulating powerful platforms due to the changes in equilibria. While a fee cap may protect small businesses’ profit margins, such a policy regulation may end up hurting them. Our findings on platforms’ shifting their promotion efforts to other restaurants should sound alarm bells about the consequences of imposing a fee cap. Policymakers should consider these second-order effects when developing regulatory policies. For instance, auditing platforms’ promotion strategies may reduce the instances where small businesses are demoted. Also, cities may coordinate their regulatory policies with those of nearby cities so that a uniform policy across borders would help prevent platforms from including businesses in nearby cities while excluding those in regulated cities. Finally, federal and local governments may also step back and think about other options to support small businesses, such as providing stimulus loans for small businesses or offering tax benefits.

This blog is based on Allen and Gang’s research, which is published in Information Systems Research and is included in the Platform Papers references dashboard:

Li, Z., & Wang, G. (2024). Regulating Powerful Platforms: Evidence from Commission Fee Caps. Information Systems Research.

Platform-Paper Updates

The Platform Papers Substack now has over 1,000 subscribers; the blog is read in 34 US states and 76 countries. Thanks!

Platform Papers is curated and maintained by Joost Rietveld.