“The crowd” can be a valuable resource for platforms

This blog is written by Johannes Loh and Tobias Kretschmer.

The internet is, and always has been, shaped by content produced by “the crowd”, that is, individual contributors providing input freely. For instance, Wikipedia has rendered traditional encyclopedias obsolete by drawing on the huge variety of knowledge provided by (more or less) regular users who spend their time writing articles, seemingly out of the kindness of their hearts. And the content they provide is of high quality: As early as the year 2000, a crowd of “clickworkers” helped NASA classify images from Mars to determine the planet’s age – they did as good a job as trained scientists. Since then, platforms have tapped into this resource in many ways: Firms like Starbucks and Doritos have launched high-profile crowdsourced promotional campaigns, Lego and Threadless let users design new products, and Uber or Airbnb – as well as virtually all e-commerce platforms – rely on user-written reviews to establish trust between service providers and consumers. Clearly, the idea of involving the crowd in a platform’s value creation activities is intriguing, as it can constitute a source of content that is both of high quality and variety. In addition, users typically volunteer their time and effort for free, making it a low-cost resource as well.

Leveraging “the crowd” for competitive advantage is challenging

Research has looked into what drives these volunteers to become active in the first place, and it has identified a wide range of non-pecuniary sources of motivation. For example, some contribute to open-source software development because they see the need for a particular solution which is not provided by firms or because they want to hone their skills. Others become active for the social benefits it provides: They enjoy working with other like-minded volunteers and attaining a position of high social status within their online community. While these motivational sources can substitute for financial incentives – platforms do not have to pay their contributors – they also make it challenging to both attract and manage the crowd. First, crowdsourced platforms are usually subject to strong network effects – the larger the community, the stronger the social benefits. This generates “winner-takes-all” dynamics and platforms will have to fiercely compete for participation. And second, because volunteers participate for their own enjoyment, it is challenging to direct them towards activities the platform owner has in mind. Put simply, they alone choose if, when, and to what extent to contribute, not beholden to the interests of the platform that hosts them. Hence, while the crowd has the potential to be a valuable resource, it is highly uncertain that platforms are able to actually leverage it for competitive advantage.

An open question: How are platform competition and contributor activity interrelated?

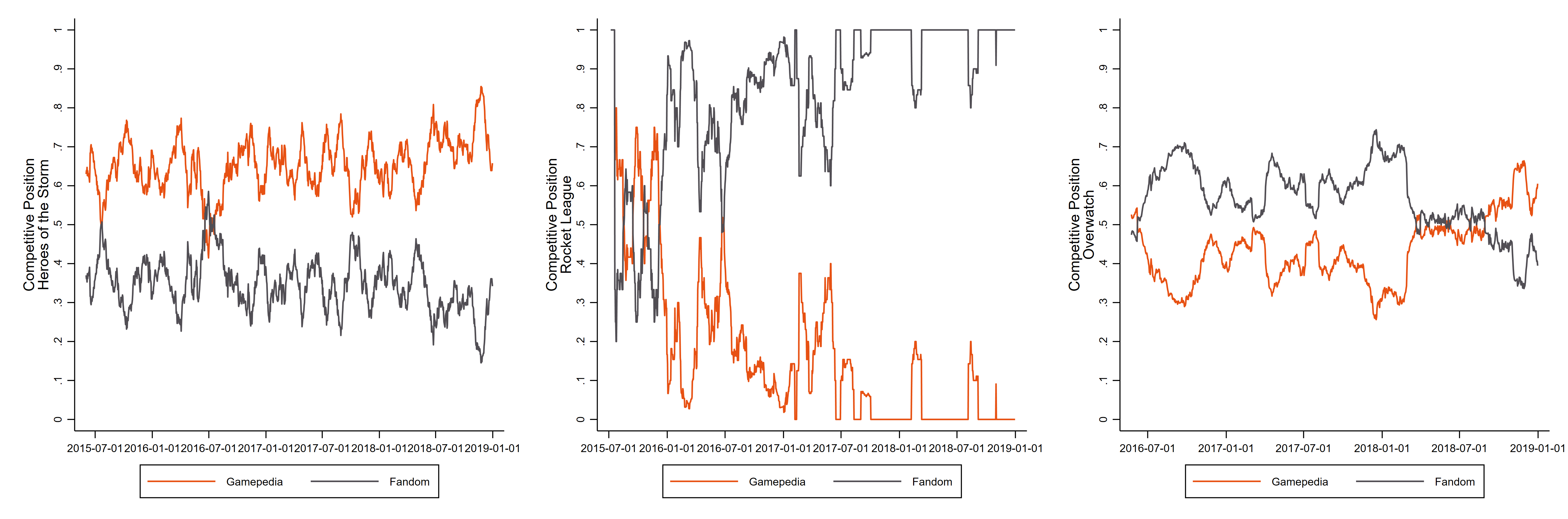

Which, then, are conditions that can lead to the crowd actually being a source of competitive advantage for platforms? This is the broad question we seek to answer in our article “Online communities on competing platforms: Evidence from game wikis” published in the Strategic Management Journal. We study two competing platforms, Fandom and Gamepedia, that host several crowdsourced game wikis. Similar to Wikipedia, community members write and maintain articles about different games that can be read by the public. However, instead of being one single repository of knowledge, wikis in our setting are distinct entities that cover a single game and that are maintained by distinct online communities. In addition, both platforms have a strong interest in hosting large, well-maintained wikis to attract an audience which they monetize via advertising. A key feature of our study is that their ability to attract such communities varies substantially across different games. That is, Gamepedia has an advantage in the coverage of some games, and Fandom in the coverage of others. To answer our research question, we investigate how the activity and contributions patterns of these online communities differ between more and less successful domains (as represented by games coverage).

Activity and contributions patterns between more and less successful crowdsourced platforms

In our study, we identify four conditions under which the crowd can provide a platform with a competitive advantage:

Success breeds success: Not unlike other types of platforms – such as e-commerce or social media – having a strong competitive position today will help in attracting and motivating subsequent volunteer activity. There are two reasons for this: First, new contributors are more likely to join a more active and well-maintained community. And second, a better competitive position comes with greater non-pecuniary benefits for contributors – they reach a larger audience with their content, and they can collaborate with a greater community.

“Personpower” matters most: Community size is the single biggest factor that determines a platforms’ competitive advantage. Having more community members contributing means more content on the platform – it is as simple as that. Further, it outweighs any advantages arising from network effects or non-pecuniary benefits which can drive individual contributors’ activity.

Social benefits also matter: Each individual volunteer contributes more in a larger wiki community. This can be attributed to social benefits, that is, they enjoy collaborating with like-minded peers. Hence, crowdsourced platforms are subject to direct network effects arising from these non-pecuniary sources of motivation.

High-productivity contributors (HPU) are more active on platforms that are in a stronger competitive position, regardless of community size. This is not the case for other community members (Non-HPU). This suggests that high-productivity contributors are driven by the satisfaction and sense of accomplishment connected to maintaining the content on the “winning” platform. (Image source: The Authors) Contributor heterogeneity matters: Not all community members are equally active. In fact, most content is produced by a fairly small group of high-productivity contributors in each community, and failing to attract (or retain) them will jeopardize a platform’s competitive standing. In addition, this very important group of core contributors does not seem to care much about the community aspect of crowdsourcing. Instead, they are driven by the satisfaction and sense of accomplishment that comes from contributing to the “winning” platform. Moreover, not only are high-productivity contributors the greatest content producers, but they also engage in policing and maintenance activities to ensure the high quality of their wiki.

What can owners of crowdsourced platforms do to attain a competitive advantage?

These four conditions have implications for potential strategies that platform owners can pursue to attain an advantage. First, community size and the presence of high-productivity contributors are the most important factors. However, neither are easily attained or imitated. Instead, acquiring a competing platform may be a more promising avenue. As a case in point, Fandom acquired Gamepedia in early 2019 following years of coexistence and competition in the area of video game wikis. In addition, Microsoft acquired GitHub, the most popular platform for open-source software development, in an effort to tap into crowdsourcing. Second, because size in itself is more important than individual contributors’ non-pecuniary benefits, strategies aimed at growing the community fast are more important than those aimed at motivating its members. Consistent with this, interviews with wiki community members revealed a focus on search engine optimization to increase website traffic and, in turn, community growth. And finally, the reliance on high-productivity contributors is a double-edged sword. They are an important determinant of competitive advantage on the one hand. But on the other hand, interviews with community members confirmed that they do not respond well to heavy-handed attempts at directing their activities, which makes managing them challenging. Instead, platform owners have to trust their judgment and consider involving them in some decisions that affect their community.

This blog is based on Johannes and Tobias’ research published in the Strategic Management Journal, which is included in the Platform Papers references dashboard:

Loh, J., & Kretschmer, T. (2023). Online communities on competing platforms: evidence from game wikis. Strategic Management Journal, 44(2), 441-476.

Platform-Paper Updates

In this month’s Platform Papers update, some platforms for good, some platforms for bad… All outstanding scholarly contributions though:

With all the regulatory scrutiny big platforms are facing these days, we can easily lose track of the societal benefits that platforms bring. In a recent paper published in the Journal of Product and Innovation Management (JPIM), Paavo Ritala outlines how platforms can help to address ‘Grand Challenges’ by way of their coordination structures, instigation and maintenance of collective action, and generativity potential. Clearly, platforms can be a force for good!

Transitioning to the ‘bad’ then, in Management Science, Liu, Lou, and Li study the unintended consequences of advances in matching technologies. The authors argue that platforms may have an incentive to obfuscate high quality matches between buyers and sellers on their platform. High-level match quality can reveal information about the thickness of the market. If demand is thin, platform suppliers might decide to leave the platform resulting in a loss of revenue.

Continuing on this theme, Long and Liu argue in a paper published in Marketing Science that “a platform may manipulate an inferior seller’s product to appear more attractive to intensify sellers’ competition to bid for advertising and also manipulate a superior seller’s organic placement to either compensate or penalize the superior seller.” Put differently, it’s not only buyers and sellers that can at times be considered as bad actors, but also the platform itself… Yikes!

Finally, in The Journal of Industrial Economics, José Ignacio Heresi looks at platform price parity clauses (e.g., contractual clauses that stipulate platform suppliers to not offer lower prices or better terms on other platforms or their own (digital) storefronts than on a focal platform. Such clauses have been observed on Booking.com and Valve’s Steam platform). The main takeaway from the study is that such clauses aren’t great for consumers: “when price parity clauses are endogenous, they are only observed in equilibrium if they hurt consumers.”

These and several other papers were added to the Platform Papers references dashboard in the last month.

Platform Papers is curated and maintained by Joost Rietveld.