Do Spotify curated playlists influence our listening decisions? And, are these playlists biased?

This blog is written by Luis Aguiar.

Many online markets have come to be dominated by large digital platforms in recent years, prompting concerns about potential abuse of market power and stirring important public policy debates. In 2020, the European Commission announced its Digital Markets Act, a new proposal about the regulation of large digital platforms that potentially act as gatekeepers in their respective industries.1 With the ability to determine what – and how – information is provided to their consumers and the amount of exposure given to their suppliers, digital platforms are indeed well-positioned to influence which products ultimately succeed.2

Like numerous other sectors, the music industry and its structure have been drastically affected by digitization. Prior to the Internet, decisions about which songs to distribute and promote were made by record stores and radio stations in rather fragmented markets. With the advent of music streaming, a few platforms are now performing both the promotional function of radio stations as well as the revenue generating function of record stores. Because digital technologies have allowed to drastically reduce the costs of producing music, another effect of digitization has been an astounding growth in the number of new songs made available to consumers. As of 2022, Spotify’s catalogue included a total of 70 million tracks.

Against this backdrop, an important value-creating function of music streaming platforms is to help consumers find products that they like. They do so in large part by relying on playlists – which are both informative lists of songs and utilities for listening to music – to promote new as well as established songs to their users. Any user is free to create playlists on Spotify, but the most followed lists on the platform are controlled and operated by Spotify itself. Of the top 1000 most followed playlists on Spotify, 866 are controlled by Spotify, and their cumulative followers account for 90% of the followers of these 1000 lists. If these playlists affect individuals’ consumption decisions, then Spotify can play an important role in determining song and artist success, including the determination of which songs and artists are discovered in the first place. In this context, it is therefore natural to ask the following questions. First, does Spotify have power to influence users’ listening decisions, via its playlists? Second, does Spotify exercise that power in a biased fashion?

Is Spotify powerful?

In a recent paper, we explore whether Spotify has the ability to influence users’ listening decisions through its playlists. More specifically, we ask whether playlist inclusion affects the number of streams that songs receive and whether it affects consumers’ discovery of new songs and artists.

Playlists and promotion

We focus on distinct types of playlists, all operated by Spotify. First, we assess the impact of the four largest global playlists – which offer the same content to any user around the globe – on song performance. The playlists we focus on are Today’s Top Hits, RapCaviar, Baila Reggeaton, and ¡Viva Latino!, which are generally used to promote already widely known artists and songs. Because they have a large base of followers, any song that is added to one of these playlists will witness a sharp increase in the number of users exposed to it. These discontinuous jumps in followers allow us to identify a causal effect by looking at how streams change right at the time of playlist inclusion.

We estimate that the average effect of appearing in Spotify’s most-followed playlist, Today’s Top Hits, is of around 260,000 worldwide daily streams. Because songs tend to stay on this playlist for about 74.4 days, the overall effect of appearing on Today’s Top Hits is of about 19.4 million streams. It follows that about a quarter of the average streams for songs that make the playlist is caused by having made the list. And given Spotify’s recent reported payments of roughly $4 per thousand streams, this translates to about $77,000 in payments from Spotify alone.

Playlists and product discovery

Second, we consider playlists that specialize in new music, and potentially new artists, as opposed to already known songs. Every week, Spotify constructs a rank-ordered list of 50 new songs – called the New Music Friday lists – for each country in which it operates. As their name indicates, these playlists are updated every Friday and generally include songs that are literally new to Spotify, providing consumers with new information and potentially promoting the discovery of new songs and artists.

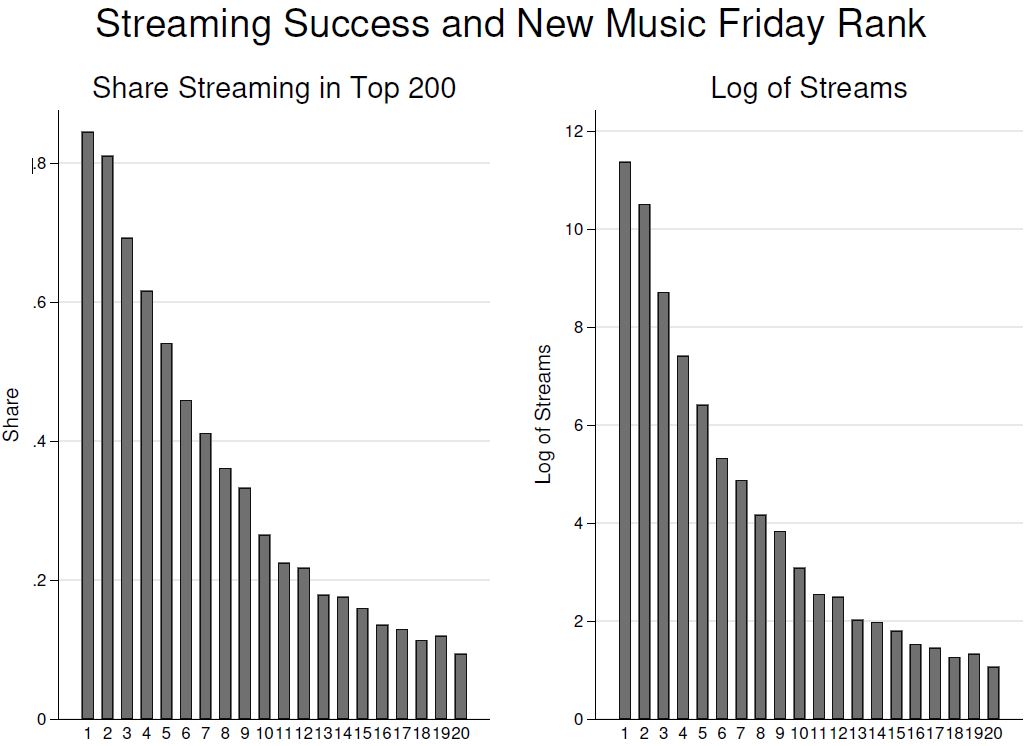

Does appearing on the New Music Friday lists increase the probability of a song’s ultimate success? Figure 1 presents the share of songs at each New Music Friday rank that ultimately appear in the corresponding country’s Top 200 streaming charts. It shows that songs with better ranks are more likely to appear in the top of the daily charts. For instance, close to 85 percent of the songs ranked #1 in a country’s New Music Friday list appear in the country’s top 200 daily streaming charts. While this suggests that high recommendation ranks matter for performance, the relationship depicted in the figure is also driven by the ability of curators to predict which songs are going to be successful. But the New Music Friday lists are also characterized by the fact that songs tend to appear in different ranks across countries. For instance, a given song may be ranked 5th on the New Music Friday list in the US, but only 16th in the New Music Friday list in Canada. Would this song be more likely to succeed in the US, where it got a better rank, relative than in Canada?

Assuming that countries have similar tastes but are treated with different rankings, we can measure the effects of the New Music Friday rankings by comparing the streaming performance of the same songs in different countries where they have received different rankings. We find that songs that obtain a #1 rank on the New Music Friday lists are about 50 percent more likely to appear in the streaming charts (relative to a song ranked 50th) and this effect falls sharply with the rank, to about 18 percentage points at rank 10 and to about 4 percentage points at rank 20. Focusing on new artists only provides similar results, indicating that the New Music Friday lists indeed help in the discovery of new artists.

So Spotify is powerful, but is it biased?

The above analysis shows that Spotify – through its largest playlists – has the power to influence artists and their products’ commercial success. But does Spotify exert this power in a biased fashion? Of particular interest is the question of whether major and independent music labels are treated differently by Spotify. While the platform does not own any of the music in its catalogue, major labels do have ownership stakes in Spotify, which could give the platform incentives to provide advantageous promotion of their products.

In a recent paper, we ask whether the rankings of the New Music Friday lists are biased against music from independent labels. We assume that the curators of the New Music Friday lists rank songs in order to maximize the total streams of the listed songs, which amounts to positioning songs that are expected to perform better higher up the ranks. And indeed, Figure 1 above shows that this is a reasonable assumption, and ranks assigned on the lists can therefore be interpreted as a measure of the curators’ ex-ante assessment of a song’s future success.

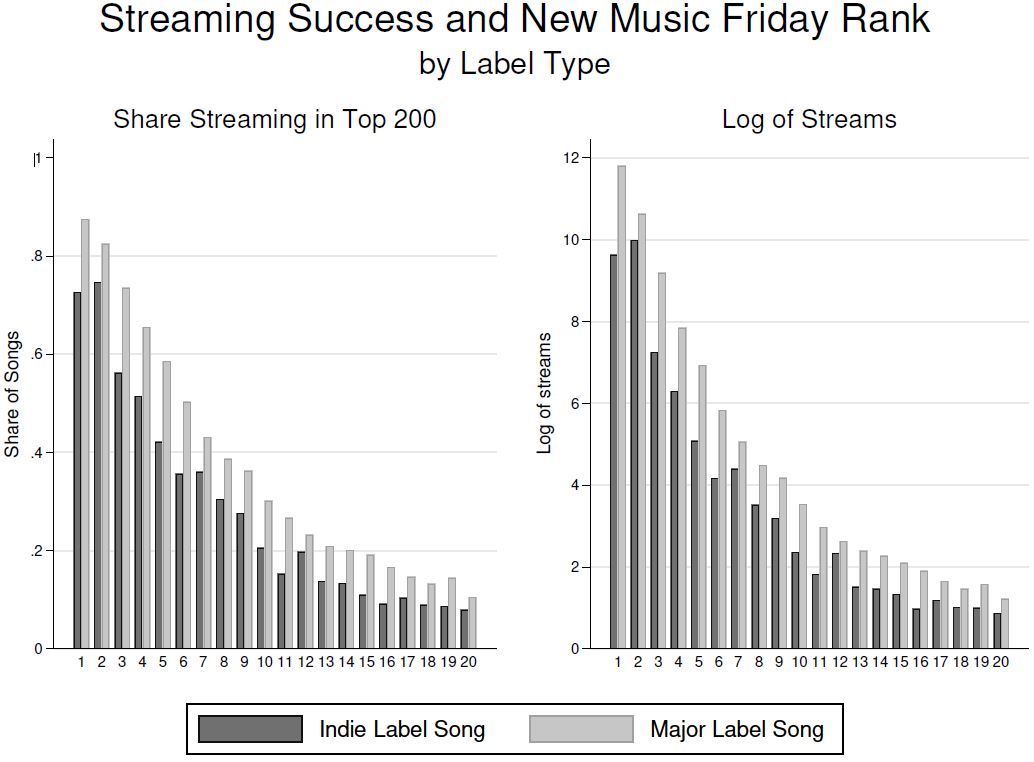

To test for bias, we can then compare the streaming performance of indie and major songs that were assessed to have equal promise (i.e. that received the same rank). If, say, major songs outperform indie songs in terms of streams, then the ranking is biased against majors since they should have been awarded a better rank. And indeed, Figure 2 shows that major-label songs stream more, conditional on the rank they are assigned.

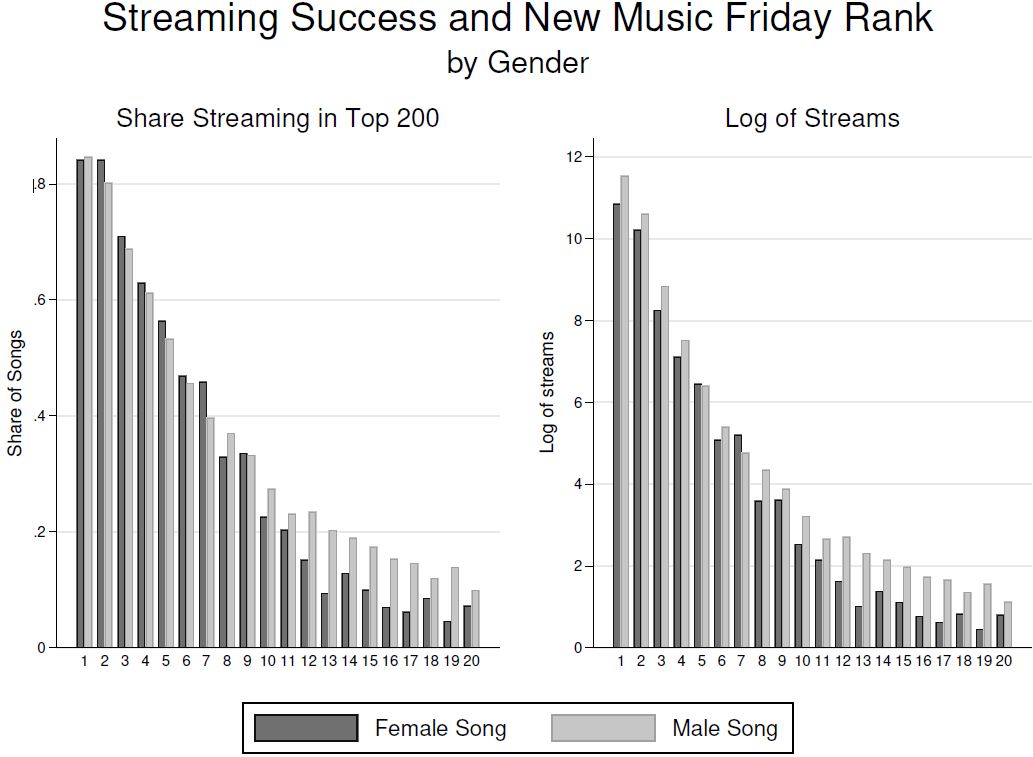

Given the important concerns about the treatment of women in the music industry, one may also consider the possibility of bias against music from female artists. What we find, perhaps surprisingly, is that songs my male artists tend to stream more than songs by women, conditional on rank. See Figure 3.

Spotify’s New Music Friday ranks therefore appear to favor music by indie artists and, to a lesser extent, music by women. Additional calculations show that curators appear to rank songs as if they valued indie streams about 40 percent more than major label streams, and music by women about 10 percent more than music by men.

It is hard to say why Spotify would behave in such a biased way, but one can speculate. It might be that promoting music from independent labels could create a more favorable environment for future streaming rate negotiation, by deconcentrating market power from the major labels. Spotify may also be responding to criticism from the industry, leading the platform to actively promote work from the groups voicing concerns.

Our analysis is naturally not without caveats. First, even if the New Music Friday lists favor independent-label music and music by women, we cannot rule out that other playlists, and other promotional activity at Spotify, favor different sorts of music. One should also be careful not to interpret our results as evidence that these groups face a generally welcoming environment in the recorded music industry.

Beyond its interest for music industry participants, our results and approach should be of relevance for observers of platforms more generally. In particular, our approach to measuring platform bias can be applied in any context where a platform ranks products, and where one can observe the ex-post success of each listing, such a click through rate.

This blog is based on Luis’ research published in the International Journal of Industrial Organization and The Journal of Industrial Economics, which is included in the platformpapers reference dashboard:

Aguiar, L., & Waldfogel, J. (2021). Platforms, power, and promotion: Evidence from spotify playlists. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 69(3), 653-691.

Aguiar, L., Waldfogel, J., & Waldfogel, S. (2021). Playlisting favorites: Measuring platform bias in the music industry. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 78, 102765.

Accordingly, one of the important concerns highlighted in the European Commission’s DMA is large platforms’ ability to provide preferential treatment to products that they offer themselves on their platform. In 2017, for instance, Google was charged by 2.4 billion euros by the European Commission for unfairly favoring some of its own services over those of competitors. See https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_17_1784.