Complementors must recognize (and mitigate) the power asymmetries and the uncertainty endemic to platform-based markets

This blog is written by Donato Cutolo and Martin Kenney.

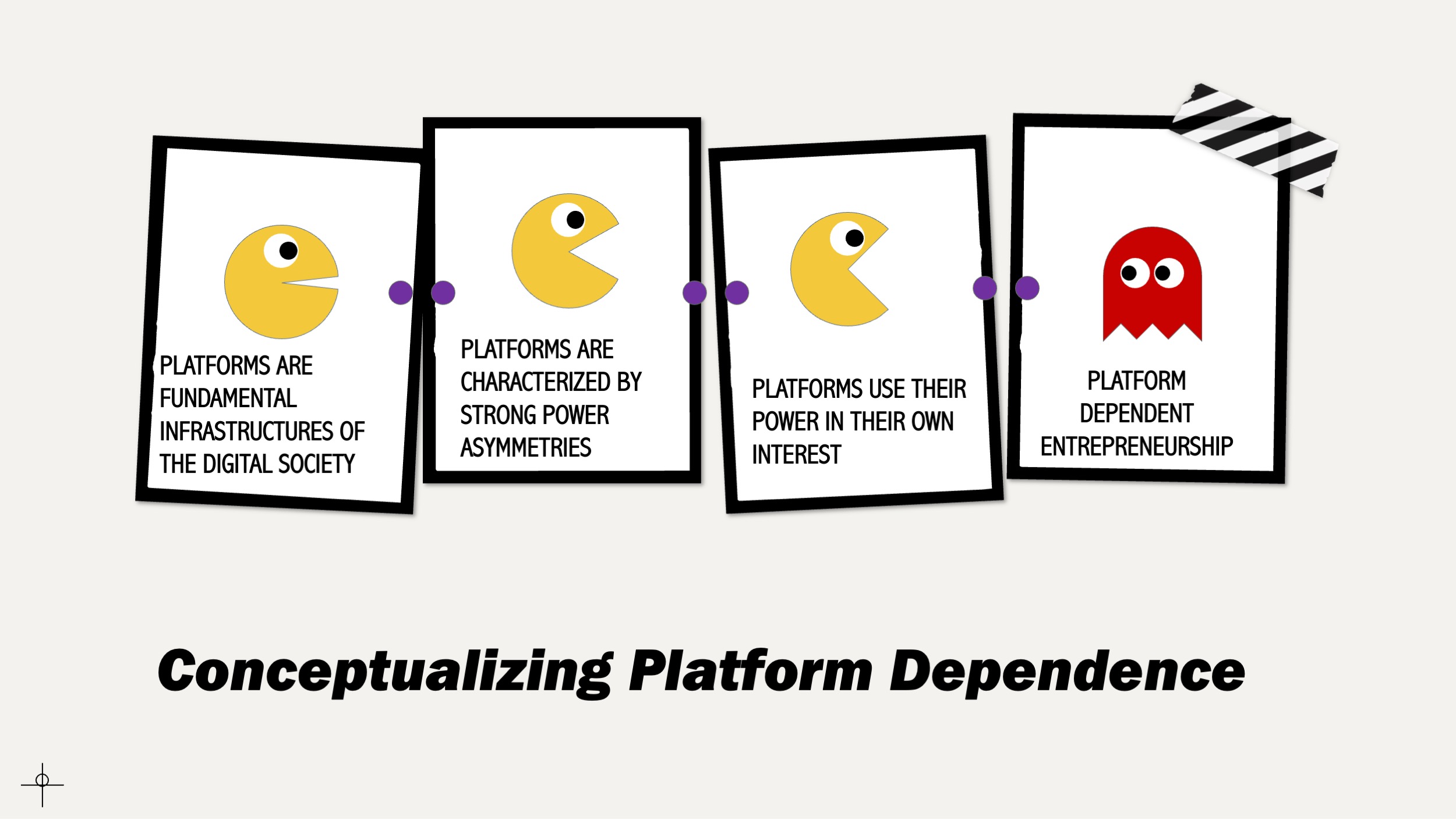

Within less than three decades, platform ecosystems have become dominant structures shaping a range of markets and industries. This is visible in the rapid growth in the number and size of online platforms offering value propositions to users and firms. The sheer size of these markets and the millions of businesses that have moved their operations to, or were created on, platforms means that we have entered what can be characterized as the Platform Economy. With this shift, online platforms increasingly mediate economic transactions and social relationships. This appears to be irreversible.

There have been tremendous benefits for both entrepreneurs and existing businesses. Platforms connect businesses to customers they could not otherwise reach and provide various tools and resources, enabling them to easily and quickly grow their business. And yet, these remarkable business opportunities create a strong dependence upon a profit-maximizing platform owner that is only responsible to its shareholders. In our article, published in the Academy of Management Perspectives, we delve into the challenges of platform-based entrepreneurship, recognizing how the power imbalances generate new risks for every complementor dependent on a platform (or considering becoming so).

Of course, the fundamental source of power for online digital platforms is their attractiveness, particularly in situations where they control access to users with a monopoly or monopsony position due to the winner-take-most aspects in many of these markets. Participation has become necessary for many companies’ survival and growth, as potential buyers and competing firms are enticed by the opportunities platform-organized markets offer. Given the winner-takes-most features of network-based industries, platform dependence increases as the availability of viable alternatives outside the platform decreases.

Platform power is ultimately embedded and expressed in its software architecture and terms and conditions. This is where the rules are embodied and where subtle changes in the software’s algorithms or terms of participation, such as fees, the earning structure, or product acceptability can nullify any business strategy. This power can be used to direct attention and orient behaviors, and, more importantly, it provides incalculable advantages to the platform. For instance, direct control of the technological infrastructure upon which all activities are conducted allows the owner to identify particularly innovations or business models that can be encouraged, emulated, or destabilized depending upon the interests of the platform.

Consider the plight of a new startup that develops an exciting, innovative app to sell through an app store. This venture is entirely at the mercy of the app store owner. To illustrate, repeatedly, Apple has embedded formerly externally provided “killer” apps into its installed software, thereby destroying that innovators “rents.” Similarly, previously approved apps have been removed unilaterally without warning, and this can occur even as the platform introduces its competitive app. The point, of course, is that in its private marketplace, the platform owner is a potential competitor that controls the rules and can rewrite the rulebook at any second.

In the case of any platform decision, appeals are routed to an anonymous, all-powerful Kafkaesque bureaucracy. The rules for generating decisions are largely opaque. In other words, all the players, many of whom are forced onto the platform due to necessity, are in a state of continuous fear, precarity, and doubt. They can appear both capricious and draconian, and all efforts to get the platform owner’s attention may be futile.

This reality means that platform-based entrepreneurs must be aware of these risks and dangers and, from the beginning, understand their options. While uncertainty has always been a defining characteristic of entrepreneurship, platforms come with new forms of uncertainty surrounding both market structure and demand that are endogenous, self-interested, and opaque: competing on platforms means competing with other complementors and potentially the platform itself. In another article, written with Andrew Hargadon and published in the MIT Sloan Management Review, we discuss some strategies that platform-based firms can experiment with to leverage the platform’s resources without becoming subservient.

One of the most potent ways a platform-based entrepreneur can address the risks associated with platform dependence is to multi-home. There are three general types of multihoming. The first is the classical case, where a firm operates through multiple platforms. The second type is channel multihoming, where a platform-based firm uses different channels, e.g., sells on a platform, operates its own website, and may even establish a physical store. Generating off-platform income streams is an important strategy to protect a platform-based business, and if extremely successful, it may allow disintermediation of the platform. The final one is platform multiplexing, where platform-based entrepreneurs adopt the different tools available from various platforms to develop new value propositions, reach new customer segments, or build new organizational capabilities that would not be possible on any single platform.

Sometimes platform-dependent firms can even join forces to collectively maximize their positions’ effectiveness and defensibility. For example, in 2018, after AbeBooks, an Amazon subsidiary, abruptly banned booksellers from several countries due to what it said was the increasing cost and complexities of operating in those countries, antiquarian book dealers from 27 countries pulled more than 3,700,000 books from the platform. After two days of protest, Amazon apologized and retreated.

Finally, and most interesting, is the fact that platform-dependent ventures are becoming more proactive and engaged with governments and the legal system. This can occur at the individual level through actions such as the lawsuit between Epic Games and Apple. But, more importantly, at the systemic level, such as, supporting the development of novel and innovative regulatory frameworks to mitigate platforms’ power. At a more systemic level, the question is whether there are solutions that maintain the benefits of platforms and sustain the incentives to generate them while protecting the community of those who buy or run a business on the platforms. Of course, building upon Karl Polanyi’s observations regarding the rise of capitalism, in another venue we argued that it is normal for the rest of society to react to a transformational change in the organization of capitalist economies with regulations to redress massive imbalances of power. While colleagues, Michael Cusumano, David Yoffie, and Annabelle Gawer recognize this and have recommended that the online platforms self-police themselves, state intervention may be necessary because, as Lord Acton, perhaps, hyperbolically, cautioned us, “power corrupts but absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Policymakers in the US, EU, China, and other jurisdictions are expanding their focus to consider the subordination of ever-greater parts of the economy to a few powerful platforms and their owners.

In sum, despite, and because of, the great opportunities offered, new and established firms are increasingly attracted and locked into platform markets and become entirely dependent upon them. As these platforms continue to intermediate ever-greater parts of the economy, entrepreneurs who depend on platforms must develop strategies to mitigate the uncertainty endemic to platform-based business environments.

This blog is based on Donato and Martin’s research published in the Academy of Management Perspectives, which is included in the platformpapers reference dashboard:

Cutolo, D., & Kenney, M. (2021). Platform-dependent entrepreneurs: Power asymmetries, risks, and strategies in the platform economy. Academy of Management Perspectives, 35(4), 584-605.