Regulating Powerful Platforms

Unintended effects of imposing fee caps on US food-delivery platforms

Platform Papers is a blog about platform competition and Big Tech. The blog is linked to platformpapers.com, an online repository that collects and organizes academic research on platform competition.

Written by Allen Li and Gang Wang.

Platform giants (e.g., Apple, Google, and Uber) often possess dominant power over other participants on the platforms (e.g., Apple vs. mobile app developers, Uber vs. independent drivers, and DoorDash vs. small restaurants). Such power asymmetry gives platform owners the edge in setting platform fees and policies to extract the surplus created by participants. Recently, tensions have intensified between these powerful platforms and third-party participants, highlighted by the ongoing legal battles and regulatory actions against platforms. For instance, Epic’s recent lawsuit against Apple accused that the Apple App Store acts as a monopoly, taking a 30% cut on all in-app purchases while banning outside payment methods. Restaurants have also complained that online food delivery apps (e.g., DoorDash and Uber Eats) charge commission fees as high as 30% of sales from delivery orders, eating up their already thin margin. Local and state regulators in the United States have introduced various measures to protect small restaurants, including imposing a cap on what delivery apps can charge restaurants. Ridesharing apps Uber and Lyft have long been accused of underpaying contract drivers, promoting some cities like Minneapolis, Minnesota, and New York City to impose minimal wages these apps need to pay drivers.

“In the EU, the United States, China, and other parts of the world, it has become a consensus that powerful platforms should be regulated. However, there have been heated debates on how to regulate these powerful platforms.”

In the EU, the United States, China, and other parts of the world, it has become a consensus that powerful platforms should be regulated. However, there have been heated debates on how to regulate these powerful platforms. The hard questions are: do regulations work? How do platforms respond to these regulations? For instance, what if regulators impose a cap on fees that platforms can charge small businesses? As digital platforms are quickly evolving, legislatures still have a limited understanding of the potential consequences of such regulations. The lack of empirical evidence hinders the progress toward evidence-based policymaking.

In a recent study of the restaurant industry forthcoming at Information Systems Research, we provide insights into the intended and unintended consequences of regulating online food delivery platforms. The global online food delivery market is a $121 billion business in 2022, and the market is projected to reach $250 billion by 2028. However, high platform fees have increasingly sparked concerns from not only restaurant owners but also policymakers. To support local restaurants, on April 13, 2020, San Francisco became the first city to order delivery platforms to cap their commission fees at 15%, which is about half of the original rate. The regulation covers independent restaurants but not chain restaurants. Similar measures are imposed by dozens of other cities such as Los Angeles, Seattle, Washington D.C., and New York City. Although many of these cities considered commission caps as an “emergency order” to protect small businesses that were hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic, some cities such as Seattle, Washington and Portland, Oregon have decided to make the caps permanent, whereas other cities like San Francisco have gone back and forth—first making the caps permanent but later reversing the action.

“This intriguing finding suggests that chain restaurants, not independent restaurants, benefit from the regulations that were intended to support independent restaurants.”

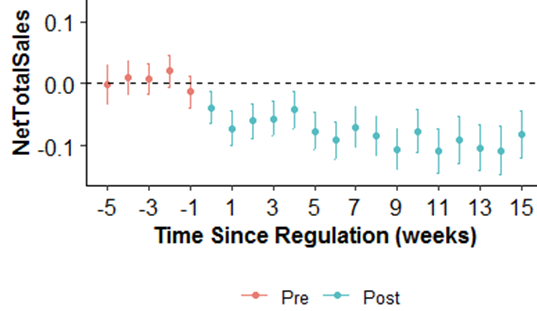

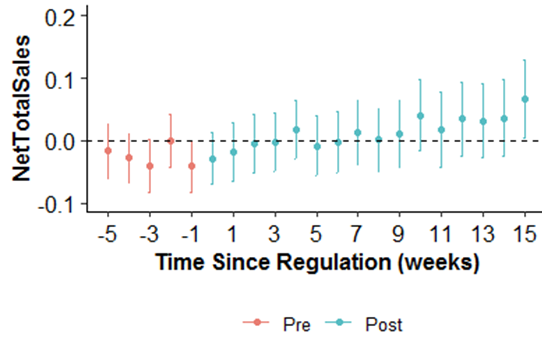

Our empirical analyses show that independent restaurants in regulated cities (i.e., those paying reduced commission fees) experience a decline in orders and revenue (Figure 1), whereas chain restaurants (i.e., those paying the original fees) see an increase in orders and revenue (Figure 2). Net profit for independent restaurants also declines, which suggests that reduced commission fees do not compensate for the loss in orders. This intriguing finding suggests that chain restaurants, not independent restaurants, benefit from the regulations that were intended to support independent restaurants.

“After cities enact commission fee caps, delivery platforms become less likely to recommend independent restaurants to consumers, and instead turn to promote chain restaurants.”

Why do independent restaurants suffer while chain restaurants thrive? Our study explores this question further by collecting additional data from delivery platforms. Our analyses show that how these platforms respond to the regulation can explain, at least partially, the negative impacts of regulations on independent restaurants. First, delivery platforms can tweak the recommendation algorithms to promote chains and restaurants just outside a city’s limits, where they can collect their rates in full. After cities enact commission fee caps, delivery platforms become less likely to recommend independent restaurants to consumers, and instead turn to promote chain restaurants. Second, delivery platforms increase their delivery fees for consumers in regulated cities, suggesting that these platforms attempt to cover the loss of commission revenue by charging customers more.

“Policymakers should consider these second-order effects when developing regulatory policies.”

Alterations of commission fees have also been observed in other platform markets such as Ticketmaster, Steam, and iOS/Android app markets. For instance, facing regulatory pressure, in 2020, Apple reduced its commission rate to 15% for small app developers if they earned up to $1 million in proceeds during the previous calendar year. Our empirical findings highlight the complexity of regulating powerful platforms due to the changes in equilibria. While a fee cap may protect small businesses’ profit margins, such a policy regulation may end up hurting them. Our findings on platforms’ shifting their promotion efforts to other restaurants should sound alarm bells about the consequences of imposing a fee cap. Policymakers should consider these second-order effects when developing regulatory policies. For instance, auditing platforms’ promotion strategies may reduce the instances where small businesses are demoted. Also, cities may coordinate their regulatory policies with those of nearby cities so that a uniform policy across borders would help prevent platforms from including businesses in nearby cities while excluding those in regulated cities. Finally, federal and local governments may also step back and think about other options to support small businesses, such as providing stimulus loans for small businesses or offering tax benefits.

This blog is based on Allen and Gang’s research, which is published in Information Systems Research and is included in the Platform Papers references dashboard:

Li, Z., & Wang, G. (2024). Regulating Powerful Platforms: Evidence from Commission Fee Caps. Information Systems Research.

Platform-Paper Updates

The Platform Papers Substack now has over 1,000 subscribers; the blog is read in 34 US states and 76 countries. Thanks!

Platform Papers is curated and maintained by Joost Rietveld.

Effects of Banning Targeted Advertising

Balancing user privacy and mobile app innovation

Platform Papers is a monthly blog about platform competition and Big Tech. The blog is linked to platformpapers.com, an online repository that collects and organizes academic research on platform competition.

This blog is written by Tobias Kircher and Jens Foerderer.

When using apps on your smartphone, how often do you encounter advertisements suggesting products that you’ve recently viewed online? It’s a bit spooky, isn’t it?

This is known as targeted advertising, a strategy that customizes ads to individual users based on a variety of factors, including their demographic information, browsing behavior, and geographical location. The data is obtained from apps on users’ smartphones and it is often aggregated by third-parties into user profiles.

“[B]anning targeted advertising could deprive developers of an important revenue model, lead to higher prices, less innovation, and, thus, perhaps do more harm than good for consumers.”

People have expressed growing privacy concerns over targeted advertising. Critics have dubbed it “surveillance advertising,” citing its invasive nature, as it often involves extensive data collection without users’ full awareness. Recently, there has been mounting pressure on legislators to ban ad targeting, and policy changes have been put into place to regulate the use of targeted advertisement on platforms, such as the Digital Services Act in the EU. However, developers of apps argue that banning targeted advertising would deprive them of crucial ad revenues necessary for app development. They claim that targeted ads are needed due to users’ reluctance to pay for apps. If true, banning targeted advertising could deprive developers of an important revenue model, lead to higher prices, less innovation, and, thus, perhaps do more harm than good for consumers.

The core issue is that we currently know very little about the consequences that a ban of targeted advertisement would have for developers of mobile apps.

Google’s ban on targeted advertising in mobile games for children

In a recent article published in Management Science, we seek to estimate the app development consequences of a ban on targeted advertising. We were especially interested in understanding whether such a ban will indeed curb developers’ innovation and which developers are more affected and which ones less.

From an empirical perspective, this is quite challenging to do because neither the EU nor the US has rolled out a comprehensive ban on targeted advertising. To surmount this obstacle, we adopted a nuanced approach by scrutinizing a smaller-scale scenario where a ban on targeted advertising was implemented. Specifically, in 2019, Google made the decision to restrict targeted advertising in children’s games on Google Android (i.e., for games that primarily target users younger than 13 years of age). Leveraging this as a case study, we conducted a difference-in-differences analysis to examine the effects of the ban. This involved comparing games affected by the ban (the treatment group) with unaffected games (the control group). To ensure that affected and unaffected games are similar, we compared games that were just forced to comply (i.e., games rated to be suitable for ages 10 and above) to games just not forced to comply (i.e., games rated to be suitable for ages 13 and above).

[W]e consistently observed a decrease in both the likelihood of developers shipping new features to their apps (-16.7%) and the introduction of new games subsequent to the ban’s enforcement (-36.3%).

Our investigation yielded compelling insights into the impact of Google’s ban on children’s game development, revealing a notable downturn in app innovation. Notably, we consistently observed a decrease in both the likelihood of developers shipping new features to their apps (-16.7%) and the introduction of new games subsequent to the ban’s enforcement (-36.3%). These estimates are of considerable magnitude. This decline can primarily be attributed to the diminishing advertising revenues experienced by developers following the ban.

The targeted advertising ban has generally had adverse effects, especially for games of undiversified, young, and advertisement-dependent developers. Arguably, these developers were more dependent on ad-based revenue streams and thus incurred the greatest drawbacks. One exception are top-tier games, which experienced positive outcomes. This suggests that highly rated and sought-after games may have benefited from the ban, possibly due to improved monetization opportunities or reduced competition.

Implications for platforms and policy makers

Our paper has unearthed a crucial insight: while banning targeted advertising bolsters user privacy, it leads to a downstream reduction in mobile app development, and thus, app innovation. Targeted advertising serves as a linchpin in both the advertising revenue model and app development landscape. For app developers, generating adequate ad revenues sans targeted advertising proves challenging. From our conversations with app developers we have learned that transitioning to a paid revenue model is often not feasible. Hence, targeted advertising appears to be a vital component of the advertising revenue model and an incentive to develop mobile apps.

“The quest to strengthen user privacy in digital advertising may clash with the fundamental goal of platform firms: providing a diverse range of innovative apps tailored to individual needs.”

For platform firms, our findings suggest a dilemma. Balancing user growth and app innovation is paramount for the success of a two-sided development platform. In light of the rising privacy consciousness among users and the escalating competition for privacy-focused individuals, platform firms have become increasingly interested in controlling the use of user data on their platforms. While a ban on targeted ads may address users’ privacy concerns, it poses a dilemma by conflicting with platform firms’ objective of fostering app innovation. The quest to strengthen user privacy in digital advertising may clash with the fundamental goal of platform firms: providing a diverse range of innovative apps tailored to individual needs.

Likewise, before opting for a ban on targeted advertising, our findings support policymakers to take into account the value that targeting contributes to digital markets, as well as the potential consequences for consumers. While targeted ads have garnered criticism for their privacy implications, they currently serve an essential function in sustaining the diversity of mobile apps. Implementing a ban on targeted ads could significantly limit consumers’ choices in mobile apps, particularly affecting startups. Policymakers must carefully weigh these considerations to ensure that any regulatory measures strike an appropriate balance between protecting user privacy and maintaining a vibrant and diverse digital landscape for consumers.

This blog is based on Tobias and Jens’ research, which is published in Management Science and is included in the Platform Papers references dashboard:

Kircher, T., & Foerderer, J. (2024). Ban Targeted Advertising? An Empirical Investigation of the Consequences for App Development. Management Science, 70(2), 1070-1092.

Platform Papers is curated and maintained by Joost Rietveld.

Smaller Slices of a Growing Pie

The effects of seller entry and demand expansion in platform markets

Platform Papers is a monthly blog about platform competition and Big Tech. The blog is linked to platformpapers.com, an online repository that collects and organizes academic research on platform competition.

This blog is written by Oren Reshef

From retail, to travel, to financing, a large part of economic activity now takes place within platform markets. In fact, seven of the top ten most valuable companies are platforms as well as more than half of the most promising start-ups. Platforms’ influence continues to grow as more and more sellers now operate fully, or at least partially, within a platform setting. An important question that rises is how does the rapid expansion of platforms affect platform participants? While consumers are likely to benefit from expansion, the impact on sellers remains unclear and has important implications to platforms’ long-term growth and sustainability.

Imagine a seller on Amazon or a driver offering rides through Uber. If Uber decided to recruit additional drivers in her area, what would be the impact on the driver? In traditional markets, the intuition should be straight forward—as more sellers enter the market, competition for consumers becomes fiercer and ultimately hurts the sellers’ bottom line. In platform markets, the analysis is more complex.

Platforms are characterized by network effects, meaning that the value of the platform depends on the number of users, both consumers and sellers. In our example, if there are only a handful of drivers in a given city, then passengers are unlikely to opt into using the platform, as it is likely to be associated with longer wait times and higher prices. As more drivers join the platform, it becomes more appealing to potential users. Simply put, if there are more things to find on the platform, then more people will search. The increase in the consumer base has the potential to indirectly benefit the driver by providing more requests. The total effect of entry is thus theoretically ambivalent: on the one hand, the total number of transactions grows, but on the other hand each seller’s “slice” becomes smaller.

Empirically answering this question poses several challenges. Simply examining the relationship between firm performance and number of sellers may lead to misleading results as sellers are likely to strategically opt into market segments with higher demand or more favorable conditions, driving a positive correlation between number of sellers and performance. Continuing with our previous example, a busy downtown area is likely to be crawling with Uber drivers, precisely because they expect to find multiple passengers in need of a ride.

I tackle this question in a recent paper published in the American Economic Journal: Microeconomics. To address the empirical challenge, I obtain data from Yelp Transaction platform (YTP), a subset of the Yelp review website that allows consumers to directly order food deliveries from local restaurants. I take advantage of YTP’s partnership with GH delivery service which came into effect in 2018. Following the partnership, all restaurants affiliated with Grubhub, at the time the largest food delivery service in the Unites States, became available on the YTP platform as well. The number of added businesses depended on the pre-partnership networks of Grubhub and YTP in various cities. It turns out that some areas experienced large overnight increases in the number of available restaurants, while other cities experienced modest or even no changes.

Consistent with the intuition provided above, I begin by documenting substantial network effects in food ordering. In areas that experienced large entry there is also a sharp increase in the number of new consumers and total transactions on the platform. Of course, these transactions are now split between more businesses.

Focusing on the incumbent businesses, those that were already on the platform prior to the partnership, reveals that the market size effect dominates the negative effect of increase competitive pressure—on average, incumbent business experienced a modest increase in revenue generated on the platform.

More interestingly, it turns out that the average increase masks substantial heterogeneities across sellers. In further analysis, I decompose the effect by the type of seller, focusing on their Yelp Star Rating, which is based on millions of reviews left by previous diners for each restaurant (in a previous paper with Michael Luca, we find that ratings capture the net value, or bang-for-buck from a particular establishment). The analysis reveals that the positive effects are concentrated at high-rated businesses who gain substantial increases in both sales and revenue (up to 15%). The increases are driven primarily by their ability to attract the new customers and retain existing ones. In contrast, low-rated business suffer a sharp decrease (approximately 10%) in their weekly revenue.

The findings above mean that gaps between high- and low-quality sellers become more pronounced as the platform grows, and the return to being high-quality grows.

How do restaurants respond to entry? The findings above mean that gaps between high- and low-quality sellers become more pronounced as the platform grows, and the return to being high-quality grows. If restaurants can improve their rating, for example by shortening delivery times, then we would expect them to have additional incentives to do so. The data confirms this intuition: Looking at the changes in ratings following the partnership, I find that entry leads existing businesses to invest more in quality and differentially improve their ratings.

What are the implications to businesses operating in platform markets and regulators? The results suggest that, as the platform adds more businesses, it doesn’t just become bigger but also, on average, better. This occurs through several channels: first, when more firms join the platform, consumers tend to choose higher quality businesses. Second, the increased competition creates incentives for firms to invest in quality, as apparent in their Star Ratings.

The restaurants on YTP had little power to block (or promote) the new partnership. However, in many other settings, such as ride-hailing services or the video game console industry, platform participants often lobby to restrict access of new suppliers. It appears that, contrary to traditional markets, the benefits from platform expansion may spillover to other platform participants, especially the top-quality ones. Moreover, if high-quality businesses thrive in larger platforms, then we can expect them to opt into larger platforms. While not the focus of this paper, this provides another channel driving the relationship between larger and better platforms.

Finally, recent regulation, such as the Digital Markets Act in the European Union and the American Innovation and Choice Online Act in the United States, attempts to reduce the power and influence of big technology firms. Antitrust regulation is a multifaceted and complex problem, which entails many, often conflicting, objectives. That said, this research highlights some of the advantages of larger, more established platforms—restricting platform size may limit the ability to enjoy some of these benefits.

This blog is based on Oren’s research, which is published in American Economic Journal: Microeconomics and is included in the Platform Papers references dashboard:

Reshef, O. (2023). Smaller slices of a growing pie: The effects of entry in platform markets. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 15(4), 183-207.

Platform-Paper Updates

A quick update before we head into the long weekend: I gave an interview for the Platform Law Blog—a blog about competition, regulation and privacy in the digital era. The PLB is a great source for everything related to digital platforms and the issues they raise for competition policy, regulation and privacy. It is run by the law firm Geradin Partners. In case you missed it, earlier this month Damien Geradin and Stijn Huijts from Geradin Partners contributed a blog to Platform Papers about the Digital Markets Act and the affected gatekeepers’ compliance plans. It’s a must read!

Platform Papers is curated and maintained by Joost Rietveld.

6 March is DMA-Day

What Europe’s game-changing regulation means for platform competition

Platform Papers is a monthly blog about platform competition and Big Tech. The blog is linked to platformpapers.com, an online repository that collects and organizes academic research on platform competition.

By Damien Geradin and Stijn Huijts, Geradin Partners

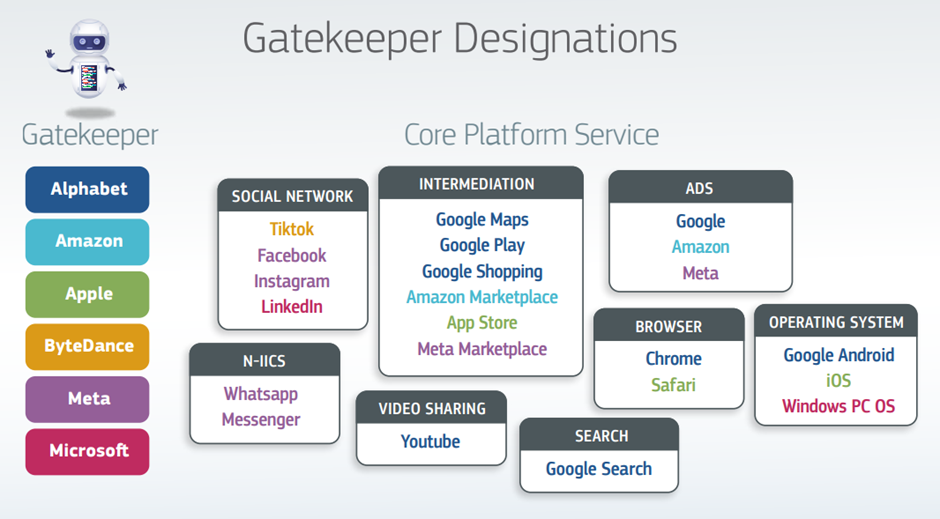

The Digital Markets Act (DMA) went into effect last year, creating a new set of rules with which some of the world’s largest digital platforms will need to comply from 6 March 2024 onwards. The DMA aims to make the markets on which these platforms have a “gatekeeper” function fairer and more contestable. Key platforms that will be affected include Apple and Google’s app stores and mobile operating systems, Meta and TikTok’s social media networks, Amazon’s Marketplace and Google’s search engine.

The platforms will be subject to a series of obligations and prohibitions to open up closed ecosystems, introduce interoperability, and ensure business users of the platforms are not treated unfairly. The Commission’s diagram below shows the gatekeepers and the “core platform services” for which they are designated.

The gatekeepers must submit their DMA compliance plans by 6 March 2024. Summaries of those compliance plans, which set out how gatekeepers intend to implement the DMA, will be made public to increase transparency and facilitate monitoring by the businesses that the DMA protects.

The DMA: A necessary and promising set of rules

How did the DMA come about? As readers of Platform Papers will know, two-sided digital platforms have particular characteristics. Network effects, scale and availability of data may mean that it can become near impossible for rivals to unseat a dominant platform, except with an entirely new service that displaces the incumbent. Moreover, some of these platforms are used by hundreds of millions of people in the EU, as well as forming the only gateway for certain businesses to serve those consumers. Finally, the owner of the platform often competes with its business users. Apple has music and TV streaming services that compete with Spotify and Netflix, Amazon retail competes with third-party sellers who use Amazon Marketplace, etc.

Network effects, scale and availability of data may mean that it can become near impossible for rivals to unseat a dominant platform.

In the mid-2010s, the European Commission and various national competition authorities launched investigations under existing competition law provisions to address abuses of the dominant positions held by these platforms. This led, for example, to the Commission’s Google Shopping and Google Android investigations, as well as its investigations into Apple’s App Store, Apple Pay, and Amazon’s Buy Box and use of data. At a national level, landmark decisions were adopted as well, including in France (Google Ad Tech), Germany (Meta), the Netherlands (Apple App Store) and Italy (Amazon Buy Box).

These investigations were influential, but also showed major flaws in the reliance on competition law to deal with deep-seated issues in digital markets. Competition investigations took a long time to resolve, so that the market had often moved on once the authorities reached their decision. They often contained remedies that were so narrow that they did not bring about meaningful change in these markets. It became clear to policymakers in the EU that competition enforcement alone would not be sufficient. Their answer was to adopt a new set of rules, the DMA, that would apply to companies that met certain criteria.

The rules themselves are both ambitious and promising. They allow the Commission to designate companies as “gatekeepers” if they have a significant impact on the internal market, provide a core platform service that is an important gateway for businesses to reach consumers, and enjoy an entrenched and durable position. In practice this is determined on the basis of quantitative requirements which, if met, create a rebuttable presumption. The relevant company is designated specifically for the relevant core platform service: Microsoft is a gatekeeper for its Windows operating system, but not for its search engine Bing. Once designated as a gatekeeper for a core platform service, the gatekeeper will need to comply with the specific rules that apply to that core platform service. They become, in effect, a regulated company.

In each case, the rules address issues identified in the competition investigations and studies carried out in the period before adoption of the DMA. For example, Apple and Google, which have been designated for the App Store and the Play Store respectively (among other services), must allow end users to directly download apps from the web and to install other app stores on their devices. They must also allow app developers to use alternative payment service providers or include a link-out to purchase in their app. They can no longer use data they obtain on their business users when competing with them. Other obligations will apply to services such as search, operating systems, and messaging services.

The proof of the pudding will be in the eating

If the rules are implemented properly and enforced rigorously, they promise to bring about real-world change in these markets. However, there are reasons to be worried about whether the DMA will fulfill that promise.

The Commission will have its work cut out, facing some of the world’s wealthiest companies who have a lot to lose from full compliance, and everything to gain from delaying the full consequences of the DMA.

Some gatekeepers have come out fighting. Three of them appealed the Commission’s decision to designate them as gatekeepers. Some also take a narrow and negative view of their obligations under the DMA. The best example is Apple, which published its plans for app distribution in Europe recently. Apple’s plans undermine the aims of the DMA to make these markets fairer and more contestable. For example, although alternative app stores will be introduced, the rules that will apply to apps that want to use them can be costly, a cost that can be avoided by sticking exclusively to the App Store. As a result, the likes of Uber, Netflix and Facebook may choose not to support new app stores, which will mean new stores will struggle to achieve the scale to compete with Apple.

The Commission will have its work cut out, facing some of the world’s wealthiest companies who have a lot to lose from full compliance, and everything to gain from delaying the full consequences of the DMA. This raises the question whether it has sufficient resources to deal with this mammoth task. While national agencies will have a role in assisting the Commission, only the Commission can make formal findings of non-compliance with the DMA. Just 150 officials are reported to be tasked with DMA enforcement at the Commission. This is not enough to regulate six of the world’s largest companies, who have near infinite resources to cause delay and obfuscation.

Immediate priorities after 6 March

Against that backdrop, what should be the Commission’s immediate priorities after 6 March? This month, the Commission will hold a series of public workshops to discuss the gatekeepers’ compliance plans. Indeed, the lessons from sectoral regulation are that empowered and well-informed stakeholders play a key role in keeping the regulated firms on the straight and narrow. It is right that the Commission views this stakeholder engagement as a priority.

If the Commission dithers at the outset, compliance issues will quickly become highly complex. Armies of lawyers and advisers will tie the Commission down in years of procedural wranglings.

But to avoid losing time and momentum, the Commission must also be willing take immediate action against those gatekeepers who are not taking compliance with the rules seriously. If the Commission dithers at the outset, compliance issues will quickly become highly complex. Armies of lawyers and advisers will tie the Commission down in years of procedural wranglings. Swift, decisive and proportionate intervention will show how seriously the Commission is taking its role under the DMA.

Third, national competition agencies must be given a serious role by the Commission. The DMA gives them the ability independently to conduct investigations if their national governments let them. The Commission should put pressure on national governments to do so. After this, the Commission and national agencies should jointly set priorities and have clear allocation principles. Alignment with the national agencies will show that Europe’s regulators speak with one voice. This will make for effective enforcement and provide more legal certainty to gatekeepers.

Finally, the Commission must facilitate private enforcement of the DMA. Private enforcement refers to businesses or consumers raising non-compliance with the DMA in proceedings before national courts. If these actions are effective, they relieve pressure from the Commission. The Commission should therefore train national courts and be ready to participate in proceedings to ensure that the DMA is applied consistently across Europe.

Geradin Partners are a specialist competition law, competition litigation and digital regulation firm based in Brussels, London and Amsterdam. Their team of lawyers is at the cutting edge of these issues having acted on many of the leading European and UK cases and held senior competition agency positions.

Platform-Paper Updates

Eight new papers have been added to the Platform Papers references dashboard in February. Here are some highlights:

You might have heard that Universal Music Group has been pulling some of its catalog from TikTok after negotiations over contract renewal reached an impasse. UMG demands higher royalty rates, protection against AI-generated music, and improved safety for TikTok’s end users. TikTok is not trying to hear it. This links with a recent study by Jiawei Chen and colleagues in Information Systems Research. Chen et al develop a deep-learning framework for music recommendations on short video sharing platforms (read: TikTok) that takes into account the three-way interaction between the creator of the video, the video itself and the music. They argue that their recommendation algorithm is superior to the ones currently in use by these platforms… That is, if there is any music to recommend, of course!

This segways nicely into another recent study in Information Systems Research by Gorkem Turgut Ozer and colleagues aptly titled “Noisebnb: An Empirical Analysis of Home-Sharing Platforms and Residential Noise Complaints.” Leveraging the phased expansion of Airbnb into different areas in New York City, the authors assess how the emergence of home-sharing platforms affects noise complaints in densely populated urban areas. The headline finding suggests that the arrival of Airbnb is associated with a significant decrease in the rate at which city residents file residential noise complaints. Perhaps there is opportunity to conduct a follow-up study that exploits the UMG-TikTok impasse as an exogenous shock to the supply of noise and influencers flooding the city!

Let me know, please, how you like today’s blogpost, which is slightly different from the usual content? We’ll resume our regular scheduled programming later this month with a blog on intra-platform competition, based on an excellent paper by Oren Resef.

Platform Papers is curated and maintained by Joost Rietveld.

Winner takes all? Blockbusters’ effect on competition in platforms

Evidence from crowdfunding

Platform Papers is a monthly blog about platform competition and Big Tech. Blogposts are written by prominent scholars based on their research. The blog is linked to platformpapers.com, an online repository that collects and organizes academic research on platform competition.

This blog is written by Zhiyi Wang and Lusi Yang.

Digital platforms are typically subject to the debate over promoting blockbusters or investing in the “long tails.” For example, Disney (or the Disney+ streaming platform) has capitalized on its library of iconic series by producing movies and TV shows within popular franchises, such as Marvel and Star Wars, to draw large audiences to its platform. In contrast, Netflix has been successful in its long-tail strategy by offering a wide variety of content, including indie films, documentaries, and foreign language content, to cater to diverse and niche interests.

The decision of a platform regarding blockbusters vs. long tails depends on the respective benefits of the two approaches. On one hand, it is clear why platforms like blockbusters: they have great potential to increase traffic, users, and word-of-mouth. On the other hand, blockbusters may intensify competition on the platform. By attracting most of the attention of users, they leave other complementors with less, potentially driving them eventually to leave the platform.

In our recent study published in Information Systems Research, we examine this tension around blockbusters on crowdfunding platforms, an emerging and open arena for entrepreneurs to launch their creative works. This work offers a different perspective with regard to blockbusters on digital platforms.

Blockbusters in Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding platforms help entrepreneurs bring their creative projects to life by asking individuals (called backers) to contribute small amounts of money. The largest reward-based crowdfunding platform, Kickstarter, has supported hundreds of thousands of entrepreneurs in achieving their goals and starting their ventures. Consistent with the platform’s objective of supporting creative and innovative works, some notable entrepreneurs have stood out on Kickstarter and gone on to play influential roles in the wider market. For example, the Pebble Smartwatch was initially funded on Kickstarter in 2012 for over $10 million. Before its acquisition by Fitbit, it was a pioneering company in the smartwatch market, establishing the key concepts and consumer expectations for wearable technology before its widespread adoption and the entry of major tech companies like Apple and Samsung. Indeed, Kickstarter has seen a few very successful entrepreneurs, and their projects have achieved overwhelmingly favorable outcomes.

The term “blockbuster” refers to a product recognized by its ability to create widespread awareness among consumers and obtain disproportionate market success.

We call these projects “blockbusters” on crowdfunding platforms. Blockbuster projects are those projects that achieve such exceptional performance that they attract great backer awareness and garner an extraordinarily large proportion of contributions. However, the tension surrounding blockbusters remains: crowdfunded blockbusters can be either beneficial, increasing the popularity of crowdfunding platforms, or detrimental, cannibalizing the funding received by other concurrent projects.

Network Effects of Blockbusters

The theoretical perspective of network effects offers us an angle to understand how blockbusters influence other projects on crowdfunding platforms. An important idea in two-sided platforms, like Kickstarter, is the cross-side network effect. This refers to the phenomenon where the size and activity on one side of the platform depend on those on the other side. On Kickstarter, creative projects attract backers to the platform, and more backers, in turn, help creative projects receive more funding.

The presence of cross-side network effects, however, is not the whole picture. Change on one side does not have to influence the other side equally or in a sustained way: instead, we may observe local and temporal network effects. For example, in the case of the Airbnb platform, an increase in Airbnb properties in a city mainly influences travelers to the city and nearby areas instead of other areas, and this increase does not necessarily influence travelers on a long-term basis because of the seasonality of traveling.

Blockbusters increase the activity and size of the backer side, which in turn benefits other concurrent projects. Further, related blockbusters exhibit a stronger positive effect on a focal project than unrelated blockbusters, and blockbusters that emerge before the launch of a focal project have a greater positive effect than those that emerge afterward.

Based on this theoretical framework, we derive several key findings with regard to blockbusters on Kickstarter. Overall, blockbusters have a positive spillover effect on other concurrent projects. Blockbusters increase the activity and size of the backer side, which in turn benefits other concurrent projects. In particular, as overwhelmingly successful projects, blockbusters increase the popularity of the platform and are of high quality, delivering positive experiences to their backers; these backers develop positive impressions and heightened expectations as to the quality of crowdfunding projects, making them likely to participate in backing other concurrent projects, which essentially drives the positive spillover effect. Further, related blockbusters exhibit a stronger positive effect on a focal project than unrelated blockbusters (local effect), and blockbusters that emerge before the launch of a focal project have a greater positive effect than those that emerge afterward (temporal effect).

How blockbusters shape crowdfunding platforms can be illustrated from a backer’s viewpoint: When there is an overwhelmingly successful blockbuster project on the platform, she is very likely to be attracted by it. After backing this blockbuster, she develops a strong positive impression and expectation because the blockbuster is of high quality and increases the platform’s popularity. As a backer, she is then likely to browse further and support other available projects. As she does so, her attention is primarily focused on related projects because she wants to find something similar to the previous success. Meanwhile, she may not do this immediately but may spend some time identifying the next creative project she wants to support. This process underlies the overall, local, and temporal effects of blockbusters on crowdfunding platforms.

Implications for Platforms

Our study shows that digital platforms or platform-like businesses should consider blockbusters or superstars as an important strategy for gaining a competitive advantage. Our findings suggest that blockbusters should be promoted on an open platform. Blockbusters not only increase the size of the user base but also drive higher participation from users, such that other complementors on the same side are able to harvest the benefits that spill over from them. This is especially the case for live streaming platforms, content consumption platforms, and e-commerce platforms offering diverse, creative, and limited-time content.

To take full advantage of blockbusters, platforms should keep track of potential blockbusters and leverage them to boost the audience and popularity of the platform. Notably, the content of blockbusters matters. Users’ attention can be directly shifted to complementors offering content related to blockbusters: platforms should be aware of such local effects to take better advantage.

In the summer of 2023, Lionel Messi joined Inter Miami in Major League Soccer (MLS). With such a superstar in the league, Apple TV’s MLS Season Pass subscription experienced 1,690% growth in the US on the first day Messi played for his new team. There was also a spillover effect on Apple TV: 15% of the MLS subscribers also became Apple TV+ subscribers. Clearly, when a superstar like Messi plays in the MLS, it immediately changes the league’s global image, making it more attractive to players and viewers. It also accelerates revenue growth and brings new sponsors to the league. Messi only plays for Inter Miami, but the “winner” is the entire league.

The power of blockbusters is everywhere, and it is not always a case of “winner takes all”: blockbusters create significant value through their spillover effects, and not only for digital platforms. For any platform-like business with multiple sides, blockbusters can be the driving force of the entire market.

This blog is based on Zhiyi and Lusi’s research, which is published in Information Systems Research and is included in the Platform Papers references dashboard:

Wang, Z., Yang, L., & Hahn, J. (2023). Winner takes all? The blockbuster effect on crowdfunding platforms. Information Systems Research, 34(3), 935-960.

Platform-Paper Updates

Today’s blog is part of a series of two blogposts that explore the tension between supply-side effects in the form of complementor competition and demand-side effects in the form of end-user demand in the context of platforms. Check back next month for Oren Reshef’s blog on how seller entry and demand expansion balance each other out in platform markets. Also see Melissa Schilling’s excellent blog on how platforms can implement some of these lessons on promotions and ecosystem orchestration.

It’s been a rather busy month for me as I am in the middle of my teaching term! This week, students are analyzing Epic Games’ transition from a traditional product business model (Epic 1.0) to a platform business model (Epic 5.0). Surely, some of them will mention Disney’s $1.5 billion equity investment in the company as the animation juggernaut looks to increase its footprint in gaming and metaverse-type experiences. It’s always great to get students’ take on real-world cases and some of their presentations are just … epic!

Anyway, eight excellent papers were just added to the Platform Papers reference dashboard, including a review of empirical studies on platform competition by Hsing Kenneth Cheng, Danny Sokol and Xinyu Zang and a paper looking at platform-endorsed quality certifications (aka promotions) in the context of Airbnb by Sanjeev Dewan, Jooho Kim and Tingting Nian.

See you next month!

Platform Papers is curated and maintained by Joost Rietveld.

The Power of Generativity in Platform Systems

When does adding many new offerings benefit or hurt a platform ecosystem?

Platform Papers is a monthly blog about platform competition and Big Tech. Blogposts are written by prominent scholars based on their research. The blog is linked to platformpapers.com, an online repository that collects and organizes academic research on platform competition.

This blog is written by Carmelo Cennamo and Juan Santaló.

Embarking on the journey of innovation is a venture filled with risks and uncertainties. From the intricate stages of research and development to prototyping and eventual commercialization, success often hinges on collaborative efforts and the integration of complementary products. Gone are the days when industry giants like Dupont, General Electric, or IBM monopolized innovation within secretive corporate laboratories. The contemporary digital landscape has shifted the epicenter of innovation to the dynamic and interconnected realms of platform-based ecosystems, where innovation thrives in open architectures and digital marketplaces.

In the latest ranking of the world’s most innovative companies by Fast Company, a remarkable paradigm shift is evident, with seven of the top ten companies being platforms. The focal point has transitioned to the pulsating heart of platform-driven ingenuity, exemplified by ecosystems like Apple’s App Store. In this era, progress is not solely dictated by the capabilities of individual corporations but by the external innovators leveraging platform technologies to continually build upon and create a stream of complementary innovations.

Enter the concept of “generativity” in platform ecosystems!

Consider the iPhone or Android-based smartphones and the plethora of apps available for users. Think about the diverse game systems and the ever-expanding variety of games. This is the essence of generativity – the power to create new opportunities for the core product technology, extending its value over time through continuous innovation efforts from third-party developers.

But if you were a buyer of early smartphones from the like of Nokia and Blackberry you must have faced a different, limited consumption experience due to a lack of compelling complementary applications. Yet, early markets for those applications existed at that time, managed by the telecommunication operators.

So, why did innovation in complementary applications fail to take off till the advent of the iPhone and Android by firms outside the telco industry?

There are multiple explanations for it. One has to do with the nature of platform systems. The simple narrative around platforms is that their value grows through indirect network effects. As a base of consumers engages with the platform, third-party firms contribute complementary offerings, attracting new customers and creating a self-reinforcing cycle. This is also why platforms are commonly seen as a special form of markets: technological infrastructures through which customers gain access to a variety of providers and their complementary offerings, while providers gain access to potential, dedicated customers.

However, these complementary innovations need to be created in the first place. The prospect of serving a large customer base is often a necessary condition but not strong enough an incentive to create the high-quality, dedicated complements that are required to attract customers to the platform. In fact, it might provide a (perverse) incentive to supply cheap versions of high-quality products and capture some demand. This is what happened in the early days of the videogame industry indeed, known as the “Atari moment”. The industry crashed because of a flooding of low-quality games supplied by developers who were attracted to the industry by the allure of the large customer base of the Atari console.

Managing platform ecosystems presents challenges, requiring coordination among diverse actors. While autonomy is a strength, aligning the interests of ecosystem members poses unique challenges. The delicate balance lies in expanding the variety of complementary offerings while preserving incentives for third-party providers to innovate and deliver high-quality complements. Stephane Kasriel, the CEO of Upwork, a freelance platform facilitating seamless access to a diverse talent pool and innovative solutions offered by freelancers, emphasizes the point:1

“If you have too many free lancers for the same number of jobs, a lot of people bid on each job. People get desperate. It’s a reverse auction system so prices go down. When prices go down, the best players exist the system and only the people that are truly desperate stay. So the quality goes down. When quality goes down, you’ve got even less demand for it. So, how do you solve that? Well, you invest in marketing strategies to try to make sure that you never have too much imbalance one way or another.”

Our Organization Science article delves into this challenge, exploring how generativity impacts user satisfaction within ecosystems.

Generativity’s Impact on User Satisfaction

We examine the video game platform industry, analyzing a dataset of new game titles launched on various consoles. Our findings support the hypothesis that generativity impacts positively user satisfaction in early phases of a platform life cycle while it can negatively impact user satisfaction as the platform matures, especially during heightened competition with other systems. This is due to two countering effects – the “free-riding effect” and the “spillover effect” – and how they unfold over time.

The free-riding effect revolves around the concept of exploiting others’ innovative effort and contribution to the ecosystem. When a platform experiences elevated generativity, third parties may be incentivized to exploit the creative efforts of others. This often leads to the development of products that mimic existing ones, yielding similar financial outcomes with reduced effort. Consider the Puzzle Game Tree, a math-based tile-swiping game created by a two-person team over 14 months of app development. Despite winning prestigious industry awards, including the 2014 Apple Design Award, the app faced rapid clones within six days of its iOS release, with some of them climbing to prominent rank positions on the App Store lists.

The spillover effect comes into play when heightened generativity marks the emergence of numerous competing solutions, signaling to third parties that the platform marketplace is expanding. This abundance is viewed as a robust indicator of increasing returns, inspiring confidence among developers to invest resources—be it money, time, or effort—in creating high-quality content for the growing platform.

Our study identifies how the free-rider effect of generativity dominates in more mature stages of a platform life cycle, leading to lower user satisfaction, increased variance in user satisfaction, lower innovation development effort, and lower marketing investments.

Implications for Business Leaders and Policymakers

As platforms mature, striking the right balance between positive reputation spillover effects and negative free-rider effects becomes imperative. Eliminating the negative free-riding effect and balancing generativity requires dynamic, adaptive governance systems. Apple’s success with the iPhone ecosystem demonstrates the importance of evolving marketplace design and rules of engagement. Apple now applies a stricter quality screening process and has redesigned how users search for apps, facilitating the discovery of new, innovative apps, and improving the overall search experience. It supports new areas of innovation either through direct collaboration with few developers investing in new functionalities of the platform or by selectively promoting innovative apps through the “app of the day” in the AppStore. Also, it changed its revenue model by pushing apps increasingly towards a subscription model and offering a 85-15 split of revenues for those providers who manage to retain their customers over a year. All of which has served to guarantee higher economic returns to developers for their apps’ quality investments, and, in turn, a great customer experience.

A key learning point of our study is that platform gatekeeping must be more permissive during the initial stages of a platform’s life cycle, and gradually intensify as the platform matures.

To the crux of Upwork’s CEO, this would imply that as the platform matures, Upwork should exert more effort in balancing supply and demand to make sure that competition among the freelancers does not spiral into a race to the bottom, which would expel the best free-lancer solutions out of the market. This is usually done by applying more stringent conditions about who can enter the platform and about the quality threshold of the solutions being provided.

For business leaders and policymakers, understanding the generativity challenge is essential. Recent regulations like the DMA in Europe address the role of platforms as marketplaces, aiming to keep markets “open” and “contestable.” However, our study suggests that viewing platform systems as mere markets undermines the organizational challenges associated with coordinating these collectives.

In conclusion, the power of generativity in platform ecosystems holds the potential to unleash innovation and unlock unprecedented value across sectors. Navigating its inherent tensions is not just an academic exercise but a practical necessity for steering sustained innovation in the digital age, leading us towards new frontiers of creativity and progress.

This blog is based on Carmelo and Juan’s research, which is published in Organization Science and is included in the Platform Papers references dashboard:

Cennamo, C., & Santaló, J. (2019). Generativity tension and value creation in platform ecosystems. Organization science, 30(3), 617-641.

Platform-Paper Updates

The paper underlying today’s blogpost was one of the most-cited Platform Papers in 2023! You can check out this and other platform fun facts in my Year-in-Review post.

Coincidentally, Carmelo and I are both on the organizing team for the 2024 European Digital Platform Research Network (EU-DPRN) conference hosted by the UCL School of Management in London, June 27 & 28. This promises to be an exciting conference where research and policy on digital platforms come together to shape the agenda for the years to come. There’s still a couple of days left to submit a paper for presentation consideration. More news about the program will follow in the months to come.

The year 2024 is off to a great start for platform competition research. Earlier this month, I added nine new papers to the references dashboard and there’s more to be added soon. Here are a few highlights:

A study by Chenglong Zhang and colleagues in Information Systems Research looks at what happens when a ride-sharing platform and a traditional car-rental firm cooperate (allowing drivers to rent cars from the rental firm to drive for the platform). Turns out, such cooperation can flood the market on the driver side lowering prices and revenues. In the end, the authors find that cooperation between the ride-sharing platform and the car-rental firm benefits riders and hurts drivers, but benefits society overall.

A study by Oren Reshef in American Economic Journal: Microeconomics studies the dynamics of same-side network effects on a platform’s seller side, or what Reshef labels the fight for “smaller slices of a growing pie”. Exploiting a quasi-exogenous shock on an online platform, Reshef studies the net effect of additional sellers expanding the market on the demand side and simultaneously increasing competitive crowding on the seller side. I find this notion of demand spillovers (and whom benefits from them) rather interesting. Luckily (for us), Oren has agreed to write a Platform Papers blog about his paper!

A study by Aparajita Agarwal and Valentina Assenova in Organization Science looks at how mobile money platforms, which allow users without bank accounts or credit cards to perform financial transactions, can fill institutional voids in certain countries. Analyzing the effects of a series of regulatory changes

that allowed nonbanks to operate as mobile money platforms, the authors conclude that mobile money platforms expand credit access to end users from formal financial institutions and thereby act as stepping stones to financial inclusion.

I hope your year is off to a great start! I have got some fascinating new blogs lined up in the next few months. See you soon!

Platform Papers is curated and maintained by Joost Rietveld.

Zhu, F., McDonald, R., Iansiti, M., Smith, A. 2015. Upwork Reimagining the Future of Work. Harvard Business School case #9-616-027

Platform Papers 2023 Year in Review

It’s been yet another record-setting year for platform competition research

This blog is written by Joost Rietveld.

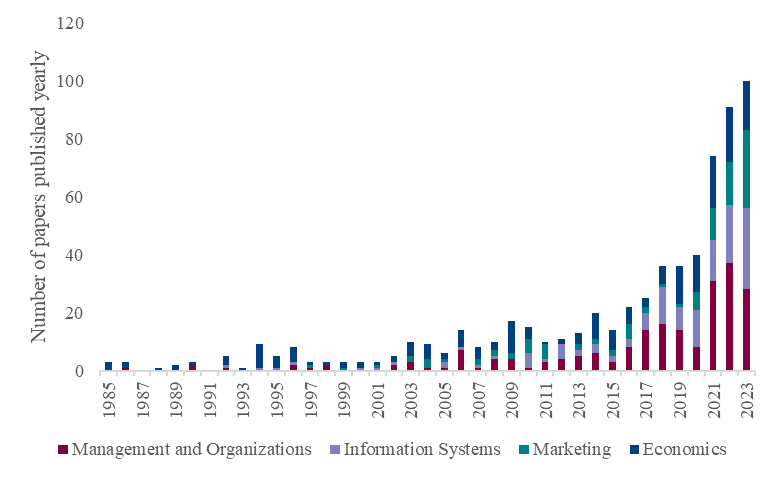

The year 2023 was another record-setting year for platform competition research. There currently are 641 published articles in the Platform Papers database—101 of those articles (16%) were published in 2023. That’s up from 91 published articles in 2022 and it represents the highest number of yearly additions to date.

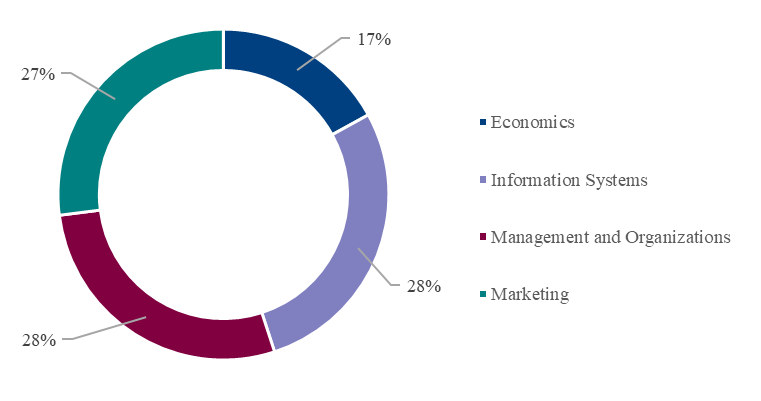

Platform competition research in marketing is on the rise. Whereas five years ago, in 2018, the share of marketing articles was less than three per cent, in 2023 marketing articles accounted for 27% of all published articles. Management and organizations (28%), information systems (28), and economics (17%) accounted for the remaining 73%.

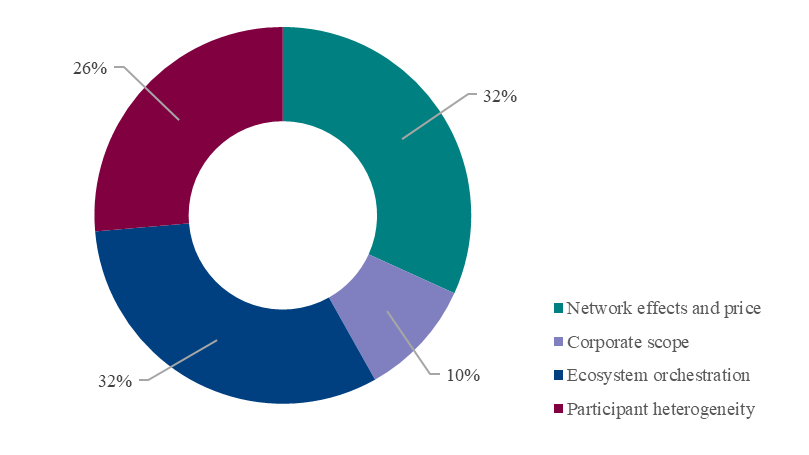

The two largest conceptual themes in platform competition research are research on network effects, platform pricing and winner-takes-all dynamics (32%) and research on ecosystem governance such as platform rule changes and algorithmic management (also 32%). However, research on network effects is down from 44% across all articles, while research on governance is up from 23%. This, in my view, tracks with recent discussions about platforms leveraging their dominance to exert unduly influence over their ecosystems. Other articles published in 2023 studied platform participant heterogeneity (e.g., the influence of superstar apps on demand spillovers; 26%) and platforms’ corporate scope (e.g., platforms’ competing with complementors; 10%). Articles can be assigned more than one conceptual theme.

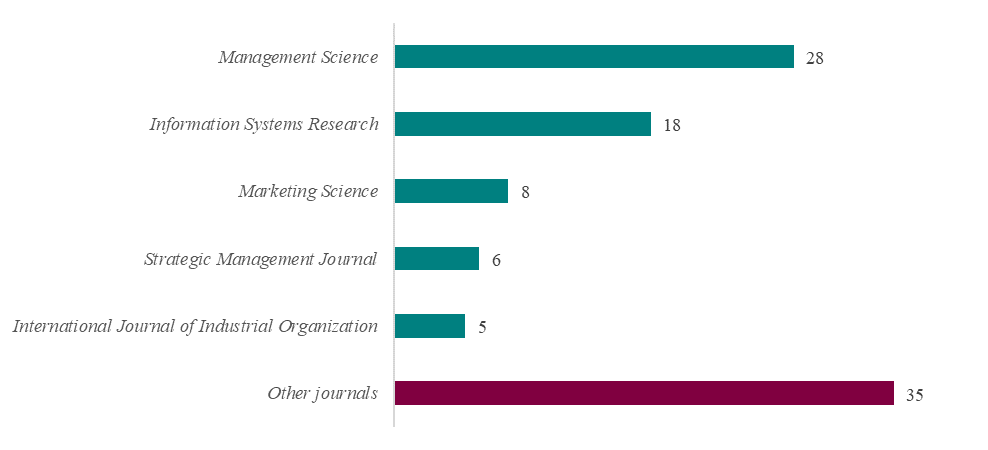

Management Science was the top journal for platform competition research with 28 published articles in 2023—a significant share of which (12 out of 28 publications) were published in the journal’s marketing department. Other popular journals include Information Systems Research (18 articles), Marketing Science (8 articles), Strategic Management Journal (6 articles), and the International Journal of Industrial Organization (5 articles). The remaining 35 articles were published in other journals such as the Journal of Industrial Economics and the Journal of Management Information Systems.

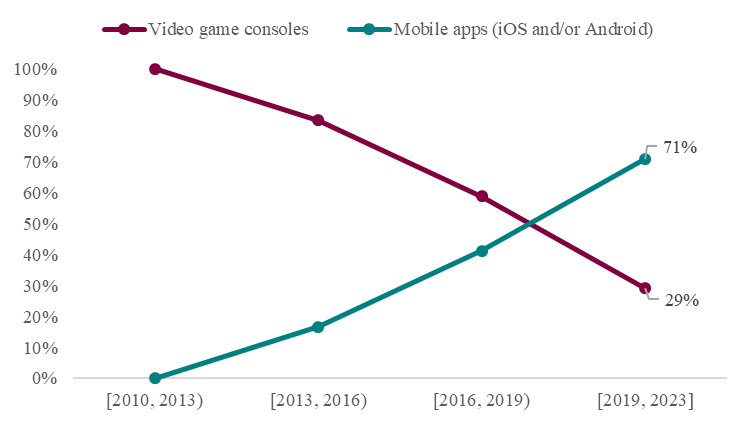

Platform papers published in 2023 analyzed a wide array of empirical contexts, ranging from Airbnb to Zillow. The empirical context that was studied most is mobile apps. In fact, mobile apps have replaced video game consoles as the “canonical” platform context. Even though research on video game consoles still is the largest empirical cluster (with 33 published articles), research on mobile apps—which, admittedly, includes a large gaming component—is now a close second (with 30 published articles). Moreover, the relative share of empirical research on mobile apps is 71% over the last four years, compared to 29% of video game consoles. The award for the most original empirical context this year goes to Farronato, Fong and Fradkin for their study on merging pet-sitting platforms, DogVacay and Rover.

Finally, the table below lists the ten most-cited platform papers by platform competition articles published in 2023. The list includes foundational articles on two-sided markets, network effects, and ecosystems, but it also includes a recent paper by Cennamo and Santalo on platform generativity and a slightly older paper by Kevin Boudreau studying competitive dynamics within platforms, between complementors. These two papers making the list could point to the growing awareness (among scholars) that the success of platforms isn’t only defined by the number of participants, but also by their contributions and engagement with the ecosystem.

Top Ten Most-Cited Platform Papers by Articles Published in 2023

Rochet, JC; Tirole, J. 2003. Platform Competition in Two-Sided Markets. Journal of The European Economic Association, 1(4); 990-1029.

Armstrong, M. 2006. Competition in Two-Sided Markets. RAND Journal of Economics, 37(3); 668-691.

Parker, GG; Van Alstyne, MW. 2005. Two-Sided Network Effects: A Theory of Information Product Design. Management Science, 51(10); 1494-1504.

Mcintyre, DP; Srinivasan, A. 2017. Networks, Platforms, and Strategy: Emerging Views and Next Steps. Strategic Management Journal, 38(1); 141-160.

Jacobides, MG; Cennamo, C; Gawer, A. 2018. Towards a Theory of Ecosystems. Strategic Management Journal, 39(8); 2255-2276.

Wareham, J; Fox, PB; Giner, JLC. 2014. Technology Ecosystem Governance. Organization Science, 25(4); 1195-1215.

Caillaud, B; Jullien, B. 2003. Chicken & Egg: Competition Among Intermediation Service Providers. RAND Journal of Economics, 34(2); 309-328.

Boudreau, KJ. 2012. Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom? An Early Look at Large Numbers of Software App Developers and Patterns of Innovation. Organization Science, 23(5); 1409-1427.

Rochet, JC; Tirole, J. 2006. Two-Sided Markets: A Progress Report. RAND Journal of Economics, 37(3); 645-667.

Cennamo, C; Santalo, J. 2019. Generativity Tension and Value Creation in Platform Ecosystems. Organization Science, 30(3); 617-641.

Some of these themes also made an appearance on the Platform Papers Substack blog this year. Below are my personal top five platform-paper blogs published in 2023:

Debunking the myth of network effects by Chiara Farronato. This blog explains why network effects aren’t always additive but also depend on the network participants’ heterogeneous preferences. Plus, it discusses the research I mentioned earlier about merging pet-sitting platforms.

Growing platforms within platforms by Agarwal, Miller, and Ganco. This blog highlights how apps and games increasingly have network effects themselves. This adds an extra dimension to platforms’ governance strategies. It’s a topic that’s key to Epic’s fight with various platforms such as Google and Apple.

Decentralized platforms and Web3 by Hsieh and Vergne. This blog balances the pros and cons of (de-)centralized platform governance. One of the main advantages of blockchain-based platforms is that they’re decentralized, but these advantages do not apply universally. Turns out, decentralized platforms need (some) centralized management, too!

Antitrust intervention in Big Tech by Thatchenkery and Katila. With all the regulatory scrutiny of Big Tech platforms these days, it’s good to see that there is research being conducted that studies the effect of such interventions. Following a regulatory intervention targeting Microsoft back in 2001, complementors’ innovation rate went up but their profits declined…

Vertical integration of platforms and product prominence in online hotel booking by Reinhold Kesler. This blog addresses a simple but important question: Are platforms more likely to prominently feature search results from providers they own? The short answer—at least in the context of online travel agencies such as Booking.com and Expedia—is Yes. Highly relevant in lightof the EU’s Digital Markets Act.

For next year, my aim is to keep updating the Platform Papers references dashboard on a monthly basis and to bring you relevant blogposts alongside platform-paper updates. I am looking forward to the 2024 edition of the European Digital Platform Research Network (EU-DPRN) conference, which will take place on my home turf in London, hosted by the UCL School of Management.

Externally, I am sure we will keep seeing plenty of platform-related news including mergers and acquisitions, antitrust investigations, and the implementation and enforcement of legislation aimed at so-called gatekeeper firms.

If you have any feedback for me about platform papers, feel free to contact me.

Happy holidays and see you in 2024!

Unlocking the Power of Freemium

When do freemium apps boost sales of their paid counterparts?

Platform Papers is a monthly blog about platform competition and Big Tech. Blogposts are written by prominent scholars based on their research. The blog is linked to platformpapers.com, an online repository that collects and organizes academic research on platform competition.

This blog is written by Yiting Deng, Anja Lambrecht and Yongdong Liu.

Digital platforms have enabled individuals and businesses to access audience and markets in unprecedented ways. Central to the success in this digital realm is the ability to monetize digital offerings. There are various methods for monetizing digital content, including freemium models, subscription models, pay-per-download or pay-per-view, and advertising.

The freemium business model, a blend of offering a “free” and a “premium” version of a product, has gained considerable traction in the digital space. Well known examples include Dropbox, LinkedIn, Spotify, etc. For mobile apps, freemium apps are those that offer a complimentary version with basic features while providing opportunities to unlock advanced or premium features for a fee. This can be accomplished by providing a separate paid premium version of the app, or more recently, through in-app purchases or subscription plans. Essentially, the free version provides consumers an opportunity to explore the app without incurring any immediate financial cost. The notion of sampling, a fundamental aspect of freemium models, is not exclusive to the digital realm. Well before digitization, merchants would distribute free samples to consumers to allow them to try the product. Similarly, in the software industry it has long been common to offer free trials. These trials typically came in two forms: time-limited trials (providing a free, fully functional version with a limited trial period) or feature-limited trials (offering a free, perpetual “light” version with restricted functionality).

In the context of freemium apps, developers typically opt for feature-limited trials. The free version grants users free access to the app’s core functionalities. For example, a freemium game app might allow users to play a few initial levels for free, while reserving advanced levels for the premium version. While sometimes users can access the premium version as a separate downloadable app, in other instances, these advanced levels can be unlocked through in-app purchases.

Despite the popularity of the freemium business model, a crucial question remains: Does the existence of a free version boost or undermine the sales of its existing paid counterpart?

Despite the popularity of the freemium business model, a crucial question remains: Does the existence of a free version boost or undermine the sales of its existing paid counterpart? On one hand, the free version provides consumers with the opportunity to try out the product before committing to a purchase, potentially driving up demand for the premium version. However, on the flip side, the free version might cannibalize sales of the paid version. So, does the availability of a free version enhance or undermine the sales of its premium counterpart? How should developers design freemium apps to increase conversion rates?

In a recent paper published in Management Science, we set to answer these questions. We compile a comprehensive and granular data set on mobile game apps from Apple’s App Store and identify apps that offered both a free version and a paid version. In our sample, the majority of freemium apps initially offered a paid version and later introduced a free version. We focus on these apps to analyze how the introduction of the free version affected the paid version’s demand. Interestingly, we find that the introduction of a free version boosts the demand for its paid counterpart, suggesting that such positive effects outweigh any possible cannibalization. It is, however, not immediately clear why the free version of the app increases the sales of the paid version, instead of cannibalizing it. To better understand why this is the case, we explore two possible mechanisms: sampling and app discovery.

The introduction of a free version boosts the demand for its paid counterpart.

Sampling

We first explore whether the free version may benefit the paid version because it allows consumers to sample the paid version before making a purchase. After exploring the free version, if the consumer enjoys the app but wants to gain access to more functions, they would then upgrade to the paid version. In this way, the free version can increase the paid version’s demand through sampling.

When would the benefits from sampling be most prominent? If, for example, information such as previous ratings indicate that the paid version is of low quality, consumers have such low expectations of product quality that it is not worthwhile incurring the hassle of sampling, and as a consequence, offering a free sample will have little effect on purchases of the paid version. Conversely, if there is information suggesting that the paid version is of very high quality, consumers may prefer to purchase the paid version directly – if they expect that the full and better version justifies its cost, they may consider it not worthwhile to go through the effort of downloading and using an inferior version. The sweet spot therefore lies in the middle: it is only for products where publicly available information, such as ratings, suggests a medium quality level that sampling matters. Indeed, we identify this inverted U-shaped relationship between an app’s average star ratings and whether the free version indeed increases demand for the paid version.

App discovery

With the very large number of available apps, one challenge for apps may be to be noticed by consumers. Statista reports that Google Play had 3.55 million apps and Apple App Store had 1.6 million apps. As a result, it may be difficult for any individual app to be visible to consumers, put differently, it is harder for a consumer to find the “needle in the haystack”. Could the availability of a free counterpart make it easier to find a paid app? We explore our data and compare categories with a smaller or larger number of available apps. Our results show that for a category with more apps, the extra visibility from a second version matters less. This makes sense: if the “haystack” is large, the relative benefit of a second app in helping discoverability is less than if the “haystack” is small. This pattern suggests that indeed the availability of two versions makes it easier to discover the app.

Balancing act: What should be free?

The success of a freemium app hinges on striking a balance between free and premium features. App developers must ensure that the free version remains useful and engaging while offering a compelling incentive for users to upgrade. How can developers strike such a balance?

In our data, we observe differences between the paid version and the free version, and analyze which differences are most effective in driving demand of the paid version. There are mainly six dimensions along which the two versions may differ:

First, the paid version allows users to progress to more game levels than the free version, such as a more complete, advanced, or challenging game experience.

Second, the paid version offers more modes or themes than the free versions. Although the ability to progress or the difficulty of the game does not change, the user experience can be customized.

Third, the paid version offers more functions or features (e.g., more powerful weapons, record keeping) than the free version.

Fourth, the paid version allows for social interactions, whereas the free version does not, such as integration with Game Center, Apple’s social gaming network, or linking to Facebook to post scores and share progress with friends.

Fifth, the paid version is ad-free, whereas the free version is ad-supported.

Finally, the paid version might provide better user support, for example, an email contact to address user questions.

We find that the positive impact of introducing a free version is particularly pronounced for apps where the paid version offers distinct additional benefits, such as extra game levels, enhanced functionalities, or a broader scope of social interactions. With such “vertical differentiation”, the free version allows consumers to experience the initial game levels with basic functionality, while the additional levels and/or advanced features provide enough value for consumers to upgrade. Likewise, the opportunity to compete, compare scores and communicate with others provides added value for those who enjoyed the initial version, making a purchase of the full version appealing. When the paid version offers more modes or themes, the free version does not affect the paid version’s demand. Such “horizontal differentiation” only changes the appearance but does not improve the gaming experience to a meaningful degree. Interestingly, if the paid version simply removes ads, an ad-supported free version has a smaller benefit, consistent with the notion that many consumers prefer ads rather than paying for content. Finally, if the paid version only provides more support, then the free version would cannibalize the paid version.

Broader implications

When we initiated the project, most freemium apps existed as two separate versions. However, in today’s landscape, it has become commonplace to have a single app version with integrated in-app purchase functions (an earlier blog covers this model). According to Statista, as of July 2023, nearly 97% apps on Google Play app store and nearly 95% apps on Apple App Store are free to download. This trend is observable in the journeys of many individual apps, such as Fruit Ninja, a popular game released by Halfbrick in 2010. Initially, Fruit Ninja Classic (known as “Fruit Ninja” before 2017) was introduced in April 2010 with a price tag of $1.99. Over time, it transitioned to being free to download with in-app purchases. At the same time, Fruit Ninja (formerly known as “Fruit Ninja Lite” and “Fruit Ninja Free” before 2017) was introduced later in October 2010 and has always been available as a free app.

While our study focused predominantly on apps with separate free and paid versions, its implications are relevant for apps offering in-app purchases and have broader relevance beyond the mobile app market. For digital firms and app developers, the study offers three salient takeaways:

First, it substantiates the effectiveness of a freemium strategy in increasing demand for the paid version of a product. Second, the results indicate that a freemium strategy is most effective for products that prior users evaluated as moderately good. Third, the findings demonstrate that to truly benefit from a freemium strategy, firms need to ensure a sufficiently large difference between the value consumers receive from the free and the paid versions to induce upgrades. In pursuit of this goal, developers should carefully consider which features should be made available for free.

This blog is based on Yiting, Anja and Yongdong’s research, which is published in Management Science and is included in the Platform Papers references dashboard:

Deng, Y., Lambrecht, A., & Liu, Y. (2023). Spillover effects and freemium strategy in the mobile app market. Management Science, 69(9), 5018-5041.

Platform-Paper updates

I am excited about the Platform Leaders Future of Digital Platforms conference later this week at London’s Science Museum. Benoit and Laure from Launchworks asked me to put together a panel on the Future of Platform Research.

In my opening remarks I will document the evolution of platform competition research by pulling some descriptive stats from the platformpapers reference dashboard (for example, mobile app stores are now the most popular empirical context for platform research, replacing video game consoles). It’s an excellent opportunity to start preparations for 2023’s Year In Review post.

My colleage JP Vergne (whose work is included in the references dashboard and who’s written an excellent blog on decentralized platforms and Web 3) and Xu Zhang at the London Business School (whose work will soon be included in the reference dashboard, surely) have kindly agreed to showcase their work at the panel.