The Role of Superstar Exclusivity

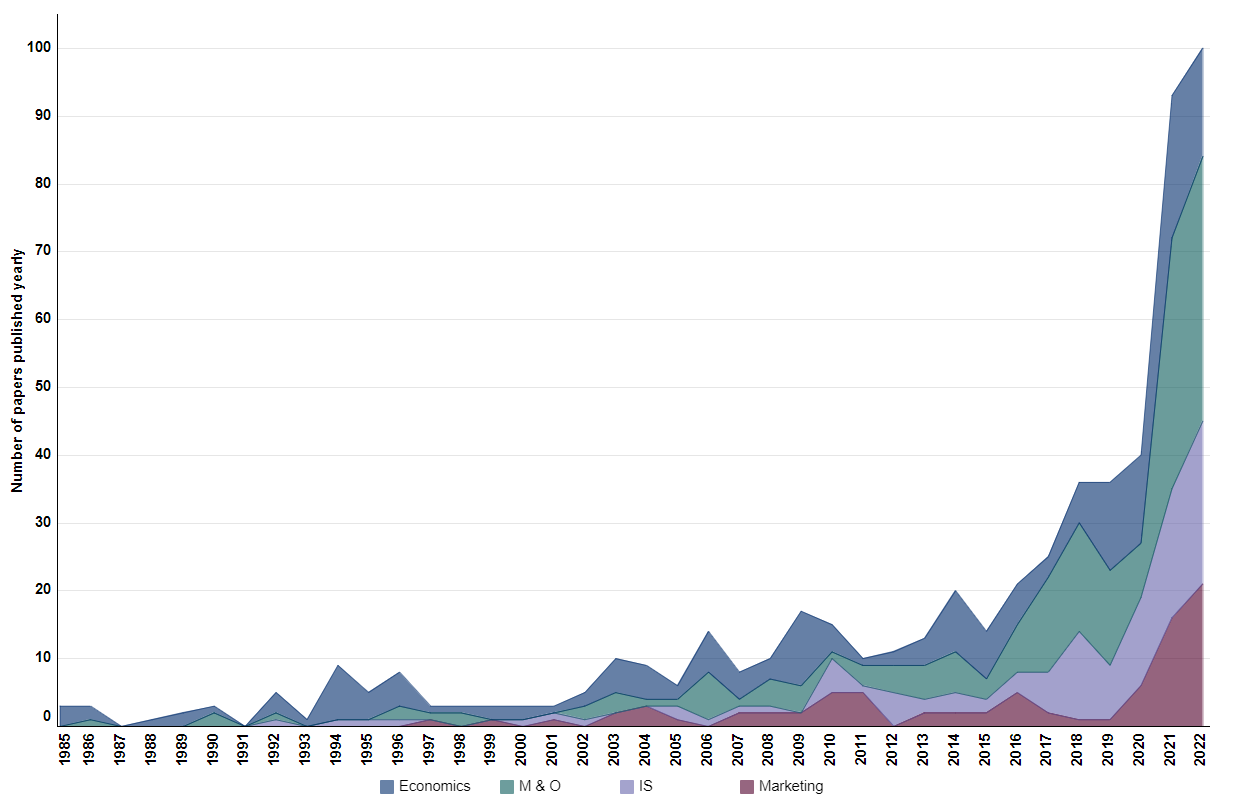

Platform Papers is a monthly blog about platform competition and Big Tech. Blogposts are written by prominent scholars based on their research. The blog is linked to platformpapers.com, an online repository that collects and organizes academic research on platform competition.

This blog is written by Elias Carroni, Leonardo Madio, and Shiva Shekhar.

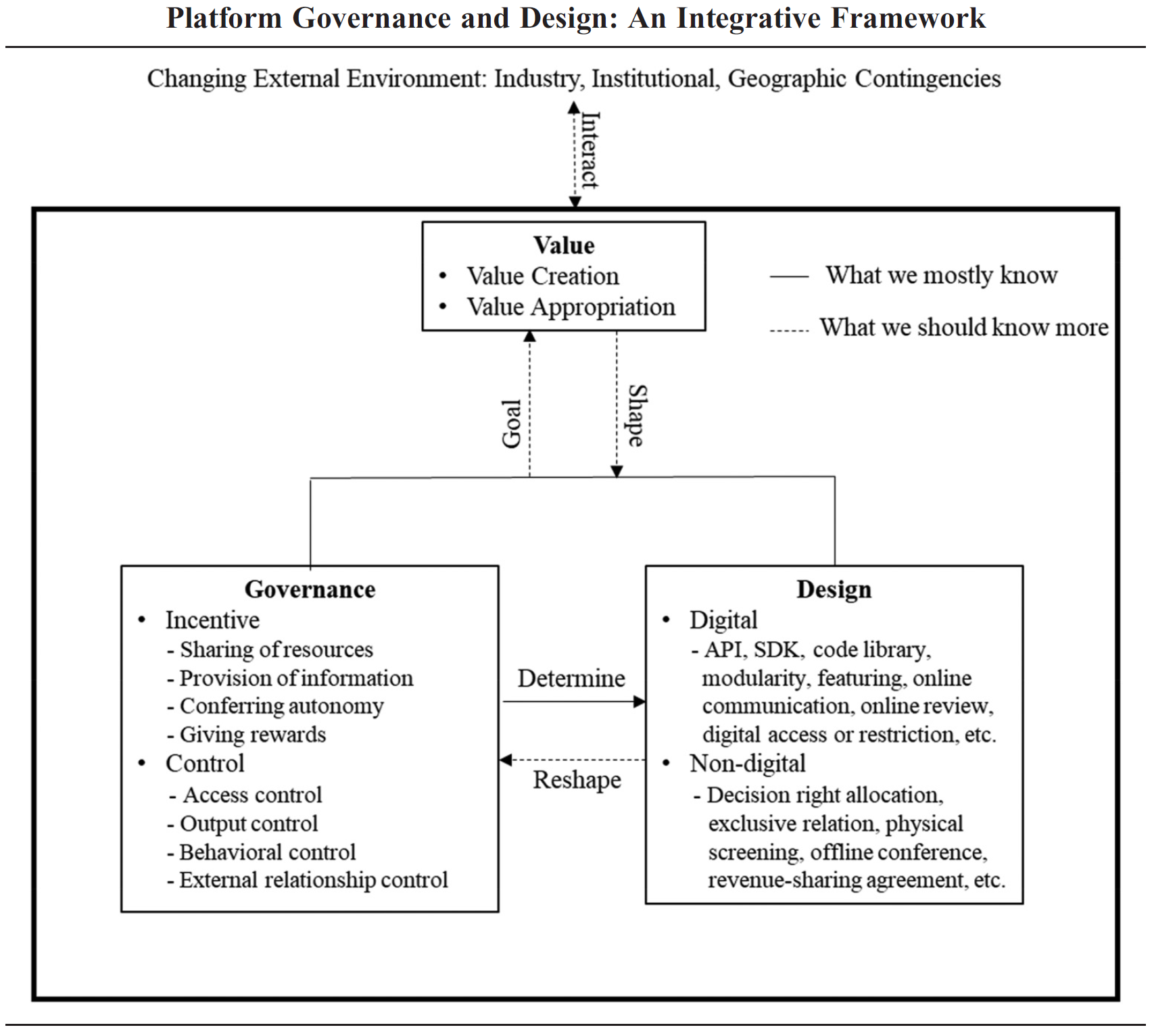

In the dynamic world of digital markets, platforms play a crucial role in facilitating interactions between various groups of agents with varying degree of market power. Some of these agents significantly influence consumer participation on a platform and can be considered superstars. Critical questions are: how does the presence of superstars shape competition between platforms, and what are the effects of platforms’ acquisitions of superstars?

The role of superstars

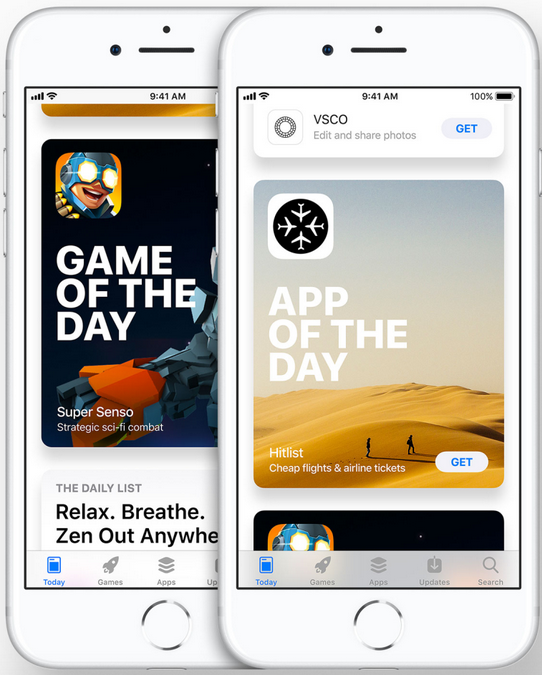

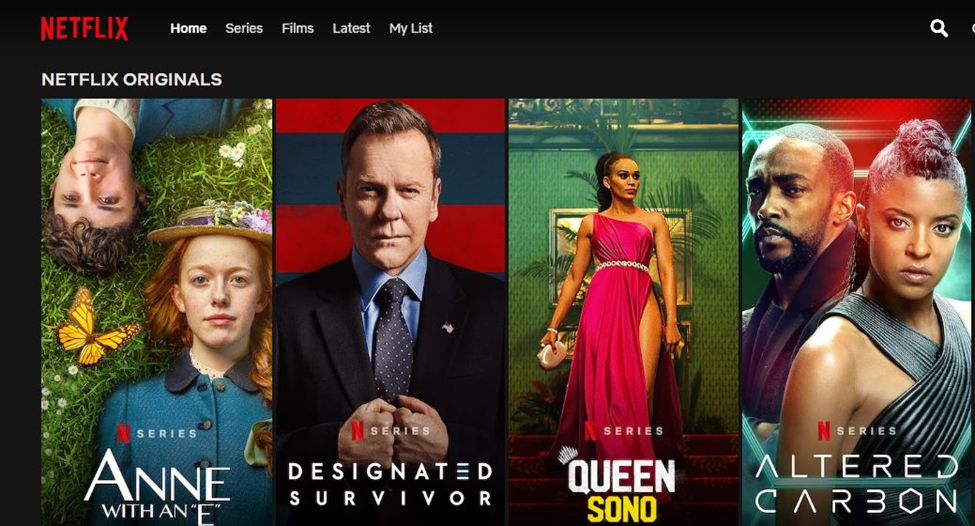

In many digital markets, platforms host a mix of professionals and “complementors”, where the former, especially superstar artists or developers, tend to be more attractive to consumers. For instance, music streaming platforms like Spotify and Apple Music feature established superstars such as Beyoncé and Taylor Swift, along with a long tail of emerging talents. Similar examples exist in mobile app markets, where popular applications like WhatsApp and Instagram coexist with independent ones and in the video-games market, where well-known gaming studios, such as Activision Blizzard and Ubisoft, among others, produce and distribute AAA+ games (e.g., Destiny, Battlefield, and the Call of Duty). The relevance of superstars on platforms extends to other domains such as open-source software, app-stores, news, and sports broadcasting.[1]

The value of exclusivity

Superstars can provide a competitive edge to platforms, particularly when they offer exclusivity to one platform over other(s). For example, in the music industry, Taylor Swift released her album 1989 under time-limited exclusivity conditions on Apple Music before making it available to other streaming platforms. Similar deals have been signed by other major artists and podcasters, and the practice has also been adopted by Apple Music’s competitors, Tidal and Spotify. In the gaming industry, Sony has several AAA games exclusive on their PlayStation consoles (e.g., God of War, The Last of Us).

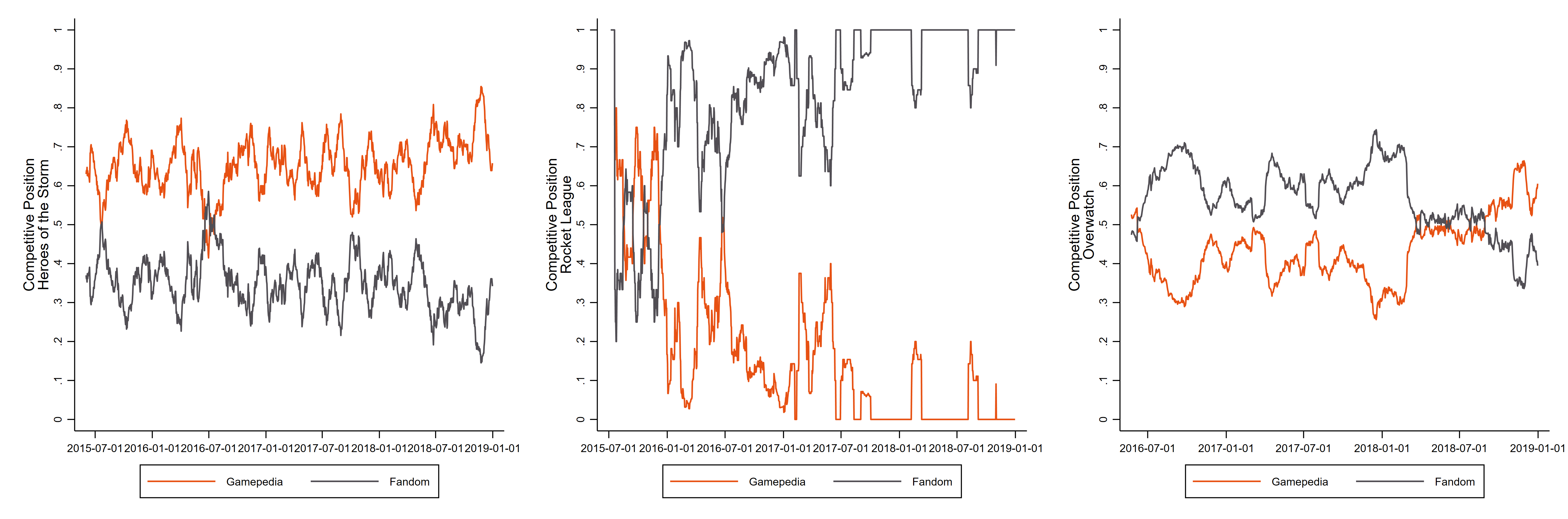

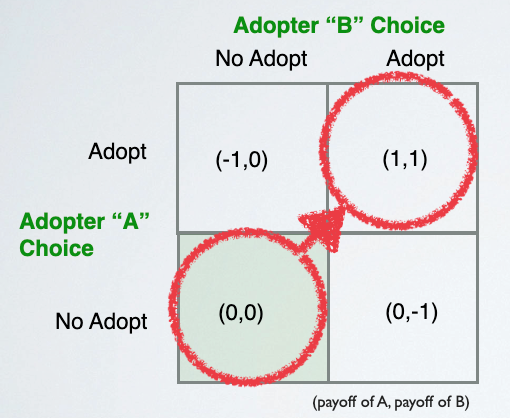

Exclusivity can enhance a platform’s market reach and allow consolidation of its competitive position because the presence of cross-group externalities can also spur within-group externalities. For instance, within-group externalities can be easily spurred by exclusivity in the video game industry due to multiplayer games, which results in the formation of communities. Indeed, many users would migrate to a platform hosting the superstar exclusively. Therefore, superstar exclusivity jump-starts a “network effects feedback loop” (see Figure 1) where more complementors also associate with the platform favored by the superstar, further attracting additional consumers. Thus, consumers and complementors tend to agglomerate on the platform favored by the superstar, resulting in direct and indirect gains and market capture for the favored platform.

From the perspective of a superstar, the exclusivity choice involves a complex trade-off. Specifically, on the one hand, by offering its product exclusively, the superstar can benefit from a more lucrative fee charged to the favored platform. On the other hand, exclusivity implies a lower consumer reach (i.e., only those consumers who patronize the favored platform) resulting in lower engagement and ancillary revenues. For instance, ancillary revenues can take the form of royalties from streaming, tickets and merchandize sales, and in-app purchases. This complex trade-off determines whether a Superstar decides to be exclusive on a platform or non-exclusive.

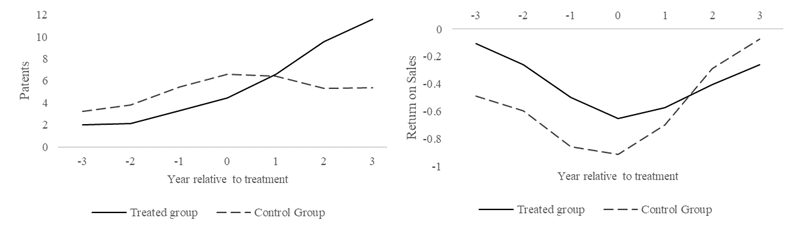

In our study titled “Superstar exclusivity in two-sided markets”, forthcoming in Management Science, we develop an economic model to analyze exclusivity decisions made by superstars and their effects on competition between platforms. In addition, we investigate how exclusivity decisions change after a superstar has merged with a platform.

Main findings

Given that exclusivity requires the superstar to limit its consumer reach, the exclusive fee charged to the favored platform must compensate for the foregone revenues achievable under non-exclusivity. We show that a superstar finds it profitable to be exclusive on a platform only if it can substantially enhance consumer participation. This jump-starts the network effect feedback loop attracting more complementors and, thus, more consumers. As a result, the superstar’s ability to charge for exclusivity increases while minimizing losses from limited market reach (e.g., foregone ancillary revenues). In contrast, if the superstar cannot attract a substantial base of consumers by signing an exclusive contract, non-exclusivity is more profitable because it allows for a wider market reach and higher ancillary revenues. We find that exclusivity can lead to welfare gains when platform market participants find it highly valuable to interact with each other, i.e. when network effects are strong.

The above discussion has important real-world implications.

In markets where consumers are not very “mobile” due to lock-in effects, a superstar has a lower ability to attract significant masses of consumers and thus jump-start the network effects feedback loop. This makes it unprofitable for the superstar to offer exclusive deals in the first place. For example, these lock-in effects exist in markets where consumers must pay upfront the cost to participate on a platform such as buying expensive electronic devices (e.g., smartphones or gaming consoles). In such markets, the likelihood of exclusive deals is expected to be lower since a new exclusive content would not trigger immediate consumer switching. Note, however, that one may still observe exclusivity in such markets. Often such exclusives are the platforms’ first party apps (e.g., Apple’s suite of apps).

In contrast, in markets where consumers are very “mobile” and have low entry and switching costs, one would expect a higher likelihood of exclusive deals by superstars. For instance, it is quite common for superstars to offer exclusivity in the music and video streaming markets, where subscription fees are low and cancellation is easy. For instance, Spotify, the largest music streaming service by volume, allows cancellation of subscription anytime.

Does superstar acquisition by platforms enhance the likelihood of exclusivity?

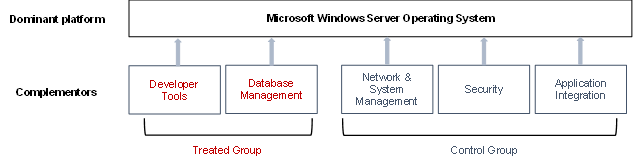

In recent times, the acquisition of a superstar by a platform has been a topic of intense discussion and concern in policy circles. A notable example is Microsoft’s proposed acquisition of Activision Blizzard, which many competition authorities initially challenged and cleared afterwards. One primary concern was that Microsoft would shut-down access to Activision Blizzard’s games for competing consoles, in particular Call of Duty.

When a platform acquires a superstar, the new merged entity (platform-superstar) decides whether to withhold access or license the superstar content with rivals. If the superstar content is licensed to the rival, the merged entity benefits from the largest market reach of the superstar content, making the platform market less competitive. Indeed, the two platforms offer the same value to consumer and there are no incentives for consumers to switch and jump start the network effects feedback loop. If, instead, the superstar content is withheld, the merged entity becomes more aggressive in the market, and this intense competition reduces the rival’s profit. Against this backdrop, the merged entity can negotiate better terms and conditions for licensing the superstar content to the rival platform. As a result, the merged entity may have fewer incentives than before the acquisition to engage in exclusivity (i.e., withholding the superstar content).

Implications for managers

There are several implications for strategies that platform owners, managers of superstars and complementors can take into account when deciding which platform to affiliate with. First and foremost, in markets with cross-group externalities, exclusivity is the most profitable choice in platform environments with sufficiently intense inter-platform competition. One way to measure the competition’s fierceness is to assess consumer preferences and their incentives and abilities to switch from one platform to another. Securing a large number of switchers is key to ensuring the profitability of such a strategy.

Second, the decision of superstars to go exclusive to one platform should be monitored closely by small complementors, who can, in turn, appropriate some of the benefits generated by the platform’s decision. Our analysis suggests that those complementors with high costs to adapt their products to the platform’s specificities can benefit the most from following the superstar and going exclusive as well. Superstar presence can help complementors break into the market and increase variety and differentiation.

Final thoughts

Understanding the dynamics of superstar exclusivity in platform competition is crucial for navigating the ever-evolving digital market landscape. To drive effective strategies and ensure balanced antitrust policies, managers and policymakers should carefully consider the power of exclusivity, the trade-offs involved, and the implications for various market participants.

This blog is based on Elias, Leonardo, and Shiva’s research forthcoming in Management Science, which is included in the Platform Papers references dashboard:

Carroni, E., Madio, L., & Shekhar, S. (2023). Superstar exclusivity in two-sided markets. Management Science.

[1] A more detailed discussion on the presence of Superstars in various market contexts can be found in the online appendix of our paper.

Platform-Paper updates

Several interesting papers have been added to the Platform Papers references dashboard in the last month. Here are some highlights:

A study on eBay’s Top-Rated Seller badges offers a nice illustration of how a platform’s selective promotion of certain sellers can spill over to the rest of the platform. In the journal of Quantitative Marketing and Economics, Xiang Hui and colleagues find that when eBay offered financial incentives to sellers with the Top-Rated Seller badge for offering fast handling and generous return policies on their listings, other, non-incentivized, sellers also were more likely to adopt the promoted behavior. This suggests that a platform’s targeted actions can have wider, ecosystem-level implications.

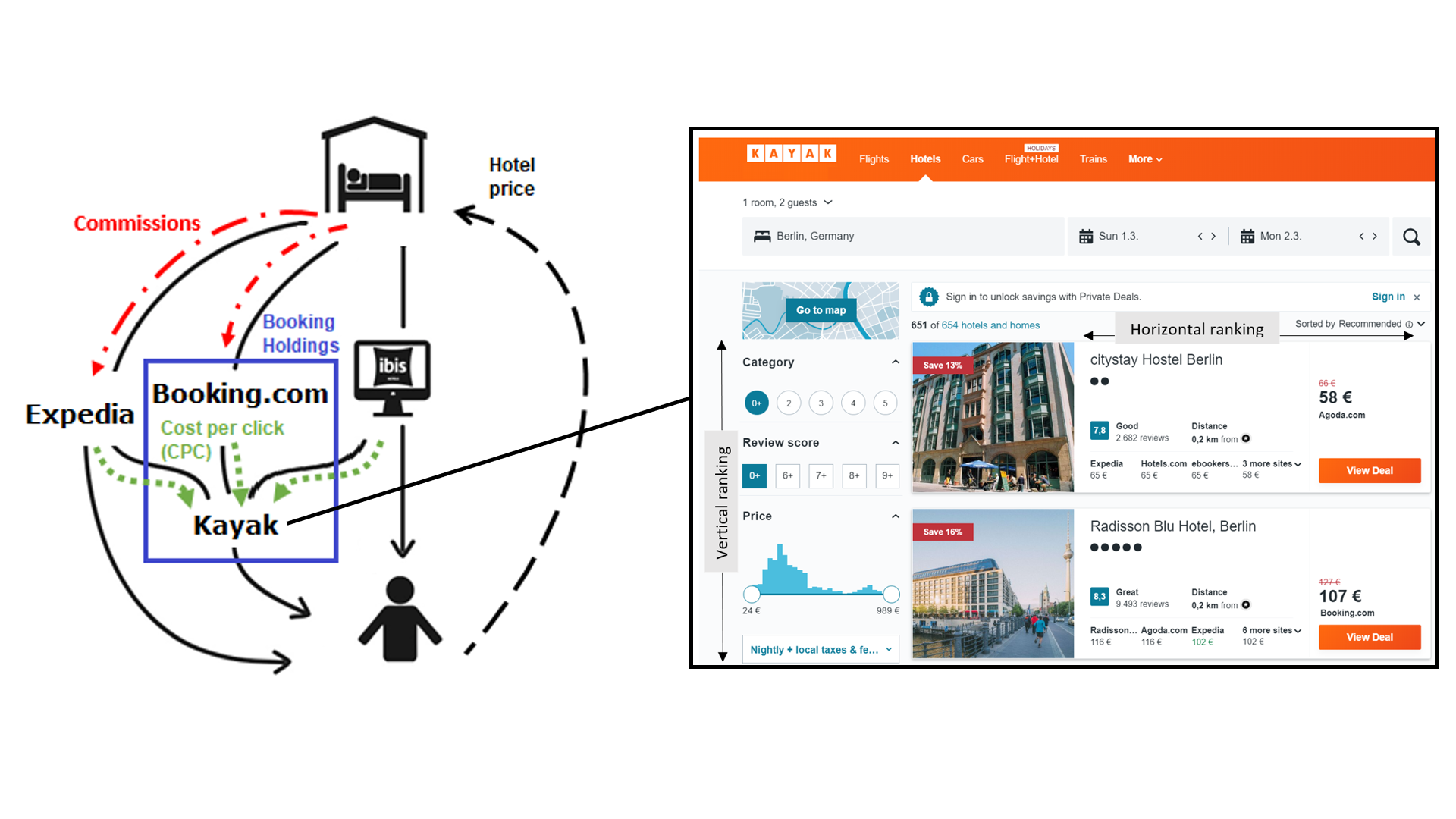

Buyers often rely on a platform’s search algorithm to reduce search costs and help them make decisions. In the International Journal of Industrial Organization, Yangguang Huang and Yu Xie study the implications of such search algorithms not being fully equal—as they often are. “If a platform adopts a highly unequal search algorithm, buyers are likely to obtain repetitive information about a small group of sellers, which causes buyers to consider fewer options and suppresses competition.” Analyzing data from food delivery platforms, the authors provide evidence that markets with less equal distributions of search results have higher average prices and more concentrated sales. They point to the design of platforms’ search algorithms as a potent avenue for antitrust regulation.

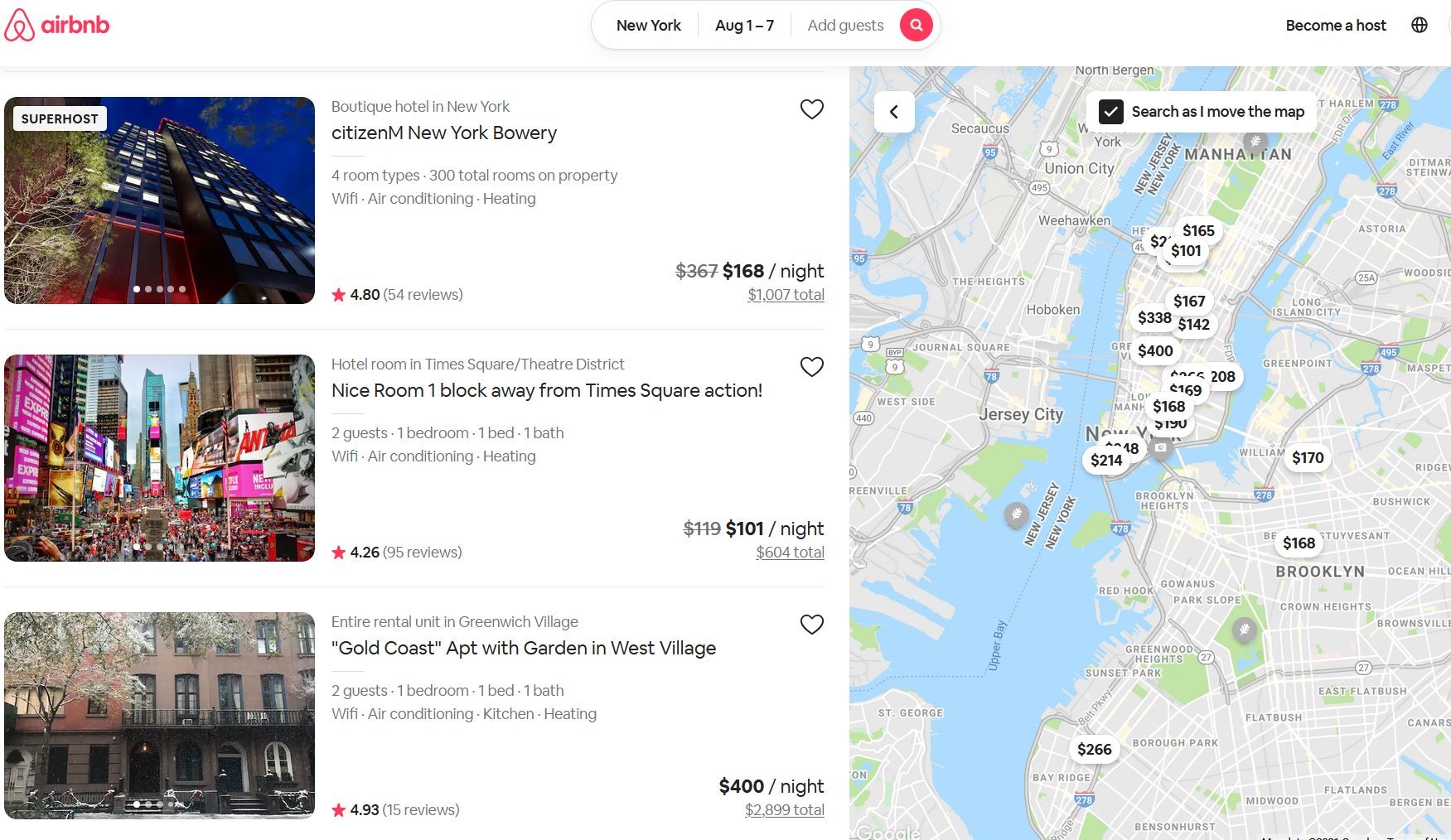

Notwithstanding the increased risk of disintermediation, allowing buyers and sellers to communicate with each other can increase the chances of a successful transaction on a platform. In the context of a peer-to-peer platform for long-term real estate rental properties, Xia Zhao and colleagues, in Information Systems Research, find that direct communication between the renter and the host can lead to the renter choosing a relatively more distinct property compared to the average property under consideration. Moreover, renters tend to be happier with their choice following their exchanges with renters, suggesting they make more informed choices.

In Management Science, Alan Kwan and co-authors study the dynamics of crowd-judging on two-sided platforms. Crowd-judging is a novel crowdsourcing mechanism whereby buyers and sellers volunteer as jurors to decide disputes arising from transacting on the platform. Studying data from Chinese e-commerce platform Taobao, the authors find that jurors tend to suffer from in-group bias: buyer jurors favor the buyer in disputes and vice versa. The extent of bias reduces with juror-level experience and when the platform dynamically allocates disputes to a diverse pool of jurors.

Enjoy the rest of your summer and see you next month!

Platform Papers is curated and maintained by Joost Rietveld.